Executive Summary

The housing affordability crisis that increasingly affects city-regions across Canada is at the centre of the policy debate for all orders of government. Municipalities, provinces, and the federal government have produced plans and strategies to address the crisis, highlighting the need to ensure proper coordination across governments.

The four papers in this report – written by academics, including legal and planning scholars, and practitioners from non-profit development – look at affordable housing, rental housing, social housing, and homelessness. They identify the ideal role of municipalities in housing policy, where municipalities currently face constraints, how other orders of government can support municipalities, and where intergovernmental cooperation is needed.

Municipalities

Two papers in the report – the first written by Carolyn Whitzman, Alexandra Flynn, Penny Gurstein, and Craig Jones; the second by Lilian Chau and Jill Atkey – emphasize the role of municipalities in setting zoning policies and approval processes that can help meet the need for housing in their regions and in facilitating the development of affordable rental housing.

Meanwhile, in their papers on social housing and homelessness, respectively, Greg Suttor and Nick Falvo both note that municipalities ought to play a major role in service delivery, given their ability to understand local needs and convene a range of local actors.

Provincial governments

Whitzman et al. note that provinces have access to important policy levers that affect housing affordability, such as rent control and vacancy decontrol. Like Chau and Atkey, they note the need to review and streamline provincial regulations on municipal action, such as any that constrain the municipal ability to loosen zoning requirements. Chau and Atkey also argue, however, that the provinces play an important oversight role and, in cases such as zoning reform, may be required to act if municipalities do not.

On social housing, Suttor argues that while municipalities should be involved in its delivery, provincial and federal governments should be responsible for funding social housing (not currently the case in Ontario). Falvo further notes the important role of provinces in funding programs to end homelessness, given the limits in municipal fiscal capacity.

Federal government

All four papers argue that the federal government’s central role is in providing funding for affordable housing, social housing, and homelessness programs. Falvo notes that current federal funding for homelessness initiatives are modest, and several of the papers point to the larger role Ottawa historically played in funding social housing in the postwar period.

Intergovernmental cooperation

All the papers emphasize that cooperation among orders of government will be required to meet Canada’s affordable housing challenge. Suttor writes of the need to restore the federal-provincial partnership in funding social housing, and Chau and Atkey similarly argue that the creation of vital housing programs in some provinces over the last 25 years has required federal-provincial alignment.

Cooperation is also required to gather data – such as assessments of housing need, as Whitzman et al. discuss, or data on outdoor sleeping, as Falvo writes – that will allow governments to address the housing challenge properly.

Ultimately, housing is also connected to many other policy areas – health care, social assistance, immigration, education, and more – that fall across all three orders of government. This makes intergovernmental coordination fundamental to successful housing policy.

1. Backgrounder: Municipalities and Housing Policy

By Tomas Hachard, Gabriel Eidelman, and Kinza Riaz

Tomas Hachard is Manager of Programs and Research at the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

Gabriel Eidelman is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, and Director of the Urban Policy Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy.

Kinza Riaz is a Master of Public Policy candidate at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy.

Introduction

Housing takes many forms along a continuum, from temporary emergency shelter to homeownership (Figure 1). Approximately two-thirds of Canadian households own their own home.[1] The remaining third either rent market-rate or non-market units, or are experiencing homelessness.

This backgrounder outlines the current role that Canada’s municipal governments play in three specific categories along the housing spectrum: private market rental housing, social housing, and services for people experiencing homelessness.

Figure 1. The Housing Continuum

Private market rental housing refers to units owned or operated by private operators (landlords, property management firms) charging market rents. Generally, “affordable” housing within this category refers to units for which rent does not exceed 30 percent of a tenant’s before-tax income, or rent is set at or below the average market rate for its particular regional area.[2]

Community or social housing refers to units developed with government funding or subsidies, and operated by either public, non-profit, or cooperative housing organizations. Such units are reserved for residents with low-to-moderate incomes, and rents are set well below market prices.

Homelessness refers to a situation in which a person or household lacks stable, safe, permanent, or adequate housing, and does not have the immediate means of acquiring it.[3] This includes people living on the streets, in emergency shelters, or in precarious locations.

All three orders of government – federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal – are involved in housing policy related to these three categories, each to varying degrees. Given this intergovernmental context, we outline how local governments work both independently and in collaboration with other orders of government to address housing challenges.

Independent municipal action within legal and fiscal constraints

Legally, municipal powers and responsibilities are set by provincial governments. Across Canada, each province and territory has its own set of legislative and regulatory frameworks that control municipal housing functions, often in highly restrictive ways. For example, the Ontario Planning Act prescribes how municipalities zone land for residential and other uses, including density permissions and building types.[4] Similarly, the Civil Code of Québec sets out rental regulations for both tenants and landlords, detailing, for example, required documentation, leasing and eviction guidelines, landlord rights, and tenant rights.[5]

Within these legal confines, local governments have considerable regulatory authority over land use and building standards, as both Carolyn Whitzman et al. and Lilian Chau and Jill Atkey note in their papers for this report. In recent years, several municipalities have attempted to accelerate the supply of affordable housing, including affordable market rental, through innovative land use planning, such as the adoption of inclusionary zoning and upzoning.

Montréal adopted a new inclusionary zoning bylaw in 2021, which requires builders to set aside between 10 and 20 percent of all new developments for affordable units (10 percent below market value).[6] This bylaw builds on similar policies adopted in 2005, which led to the construction of nearly 6,000 affordable units by 2018.[7]

Likewise, Toronto’s newly adopted inclusionary zoning policy requires private developers to secure between 5 and 10 percent of new units built near major transit stations for low-income and moderate-income households (those earning between about $32,000 and $92,000 a year, depending on household size), increasing to 8 to 22 percent by 2030.[8]

Most recently, the City of Vancouver appears ready to adopt Mayor Kennedy Stewart’s “Making Home” initiative, which would allow for the construction of up to six affordable housing units on lots where only one single-family home is currently allowed. The program targets the conversion of 2,000 lots around the city, with the potential to create up to 10,000 affordable homes for middle-income households.[9]

Canadian municipalities are constrained, however, by limited fiscal capacity.[10] They rely heavily on property taxes, and are prohibited from levying income or other more progressive taxes. Partly for this reason, most provinces play a large role in major capital projects, such as social housing. Social housing units in British Columbia, for example, are owned and operated by a provincial crown corporation known as BC Housing. Similar agencies exist in Saskatchewan (Saskatchewan Housing Corporation), Nova Scotia (Housing Nova Scotia), and Manitoba (Manitoba Housing).

In other provinces, however, such as Québec and Alberta, the financial burden for social housing is shared by municipal governments and municipally owned housing agencies. For example, more than 55,000 Montréal residents live in housing managed or subsidized by the Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal,which receives only 30 percent of revenues from provincial and federal governments.[11] Similarly, the Calgary Housing Company operates more than 7,000 social housing units, and administers another 2,200 rent-supplement arrangements, based on various shared-cost agreements.[12]

As Greg Suttor notes in his paper, Ontario is a further outlier. An average of 77 percent of social housing expenditures in the province are funded by municipal governments, compared with 14 percent and 9 percent by the provincial and federal governments, respectively.[13] Toronto is an extreme case. The Toronto Community Housing Corporation operates more than 60,000 units, housing approximately 165,000 residents, making it the country’s largest social housing provider and the second largest in North America. Yet the City currently receives no funding at all from the provincial government to support these operations. Nearly 79,000 households are currently on the city’s waitlist for social housing, further increasing demand for other forms of affordable housing.[14]

Municipal collaboration with other orders of government

Any municipally led housing initiative almost inevitably requires amendments to provincial planning legislation, demonstrating the importance of intergovernmental collaboration. Numerous housing programs and projects depend on funding from provincial governments, and increasingly, from federal investments as well.

The City of Medicine Hat, Alberta, recently announced that it had functionally eliminated chronic homelessness based on the success of its Housing First program, which places unsheltered people in long-term housing before providing mental health and addiction recovery services.[15] Larger urban centres across the country, such as Edmonton, have attempted to replicate this model. Since 2009, more than 6,000 people have been housed and supported through Edmonton’s Housing First program, and the number of people sleeping outside dropped from more than 60 percent of people experiencing homelessness to 4 percent in 2018.[16] These programs were supported by the Government of Alberta’s 10-year Plan to End Homelessness, released in 2008, which earmarked funding for community organization in Alberta’s seven major cities to deliver Housing First programming and support local homelessness priorities.[17]

Any municipally led housing initiative almost inevitably requires amendments to provincial planning legislation, demonstrating the importance of intergovernmental collaboration.

At the national scale, the Government of Canada’s $70 billion National Housing Strategy (NHS), released in 2017 and adapted since, aims to cut chronic homelessness in half, ensure that 530,000 families are no longer in housing need, and fund the construction of up to 160,000 new affordable housing units.[18]

The federal Reaching Home program provides $2.5 billion over 10 years directly to municipalities to introduce local “coordinated access” points that match people experiencing homelessness with appropriate transitional housing, permanent supportive housing, or long-term housing options.[19] (Nick Falvo discusses efforts to address homelessness further in his paper for this report.)

Similarly, the federal Rapid Housing Initiative, which dedicates $2.5 billion for urgent housing needs in response to COVID-19, is allocated directly to municipalities to help build more than 10,000 new units across the country in just 24 months, from 2020 to 2022.[20] The federal government has also entered into direct partnerships with several social housing providers, such as the Toronto Community Housing Corporation, to support renovations of existing stock.[21]

Other components of the National Housing Strategy rely on bilateral agreements signed between the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and provincial governments, which often sidestep municipal involvement. Altogether, provinces and territories have committed nearly $7.5 billion in joint funding to support the Canada Community Housing Initiative to expand and renovate provincial social housing units; the National Housing Benefit, a low-income assistance program paid directly to households to help with rental costs; as well as provincially identified priority repair and construction programs.[22] Municipal involvement in these initiatives is limited to waiving development charges and property tax exemptions for approved projects.

Conclusion

All in all, municipalities play an active role in housing policy, most notably in homelessness prevention and through land-use planning, even though provincial governments determine the extent of municipal powers in this domain. Fiscal constraints, however, limit the ability of municipal government to contribute to capital-intensive projects. As a result, it is rare for municipalities to play a large role in social housing, although Ontario is a significant exception.

Generally, provincial governments provide the largest share of funding for housing, though recent investments by the federal government suggest an evolving federal role, fulfilled mainly through federal-provincial bilateral agreements and, to a lesser extent, direct funding to municipalities.

2. Affordable Housing: Increase Federal and Provincial Funding to Support Municipal Action

By Carolyn Whitzman, Alexandra Flynn, Penny Gurstein, and Craig Jones

Carolyn Whitzman is adjunct professor at University of Ottawa’s Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics.

Alexandra Flynn is assistant professor at the University of British Columbia’s Peter A. Allard School of Law.

Penny Gurstein is the director of UBC’s Housing Research Collaborative.

Craig Jones is the research coordinator for UBC’s Housing Research Collaborative and the Balanced Supply of Housing Node of CMHC’s Collaborative Housing Research Network.

Canada is in a housing crisis. Increased housing need and homelessness, fuelled by the net loss of affordable housing, has become a top political priority. In 2018, almost 1.7 million Canadian households, one in nine, were in core housing need, meaning they lived in housing that cost more than 30 percent of their household income and/or that was overcrowded or in poor repair. Renter households were three times as likely to be living in core housing need as homeowners.[23]

By 2021, the Parliamentary Budget Office estimated that core housing need had increased to 1.8 million households, despite the 2017 National Housing Strategy’s goal of reducing housing need by 530,000 households and eradicating chronic homelessness within a decade.[24] Job losses and economic inequalities associated with COVID-19 have resulted in one in three renters worrying about making next month’s rent.[25] In Toronto and Vancouver, only 0.2 percent of apartments have rents of $625 or less.[26]

The origins of the housing crisis are multi-faceted. For instance, all three orders of government have neglected affordable rental housing while maintaining and increasing subsidies to support homeownership. An Ontario-based study found that 92.6 percent of total government spending on housing, including tax exemptions, went to homeowners.[27] Non-profit housing completions across Canada went from about 14 percent of all new homes created in the 1970s and 1980s to less than 1 percent throughout the 2000s and most of the 2010s.[28]

The impacts of affordable housing shortages are expensive for municipalities. The cost of a municipally funded individual emergency shelter bed in Toronto was $40,000 a year before COVID-19; the cost has now doubled.

In the mid-1990s, meanwhile, responsibility for maintaining and expanding social housing was downloaded to provinces and territories. Ontario, which had the largest stock of social housing, in turn downloaded this fiscal and legislative burden to municipalities as part of Local Services Realignment.[29] (For more on social housing, see Greg Suttor’s paper.)

Provincial policies on social assistance and minimum wage have put further pressure on the housing system by affecting low-income residents’ ability to pay rising rents.[30] In Ontario, social assistance rates for single adults without disabilities have not increased since 1986, after adjusting for inflation. In most provinces, annual welfare incomes were about $10,000 in 2019 dollars, with a maximum shelter allowance of $390/month.[31]

The impacts of affordable housing shortages are expensive for municipalities. The cost of a municipally funded individual emergency shelter bed in Toronto was $40,000 a year before COVID-19; the cost has now doubled. The cost of a home with on-site social support that would prevent reliance on municipally funded emergency shelters is only $24,000 a year, but would require infrastructure investment and ongoing subsidies to bring rents down to levels affordable to very low-income households.[32] Municipalities face this growing fiscal challenge with minimal funding: they receive 10 percent of all taxes collected across Canada.[33] Their revenues rely on regressive property taxes, whereby low-income renters pay more tax as a proportion of their incomes than high-income homeowners, although deferral programs exist for low-income homeowners.[34]

Although coordinated municipal advocacy on affordable housing is increasing,[35] we agree with David Hulchanski: “municipalities can only do what their provinces allow them to do.”[36] We would add that particularly in the face of climate change; continuing urbanization and sprawl; a growing global refugee crisis; an aging population; increasing disparities based on gender, racialization, Indigeneity, and abilities; and the financial impact of COVID-19, it is difficult to envision progress on affordable housing without federal leadership that demands provincial accountability and provides municipal empowerment, including new revenue sources.

This paper focuses on the role of municipalities in directly providing and steering affordable housing outcomes. While federal, provincial, and territorial governments all have vital roles to play, municipalities in particular can play important roles in four key areas:

- need assessment;

- land acquisition and assembly;

- zoning and approvals;

- preventing affordable housing loss.

The paper reviews each of these areas and concludes by stressing the importance of multi-level governance and of providing more powers to municipalities.

Measuring housing need

To begin with, governments need a consistent way to define affordable housing and measure core housing need in a way that can help them gradually implement the right to adequate housing, as mandated by the National Housing Strategy Act.[37] This definition must be

- consistent across orders of government, because the provision of housing is inter-jurisdictional;

- simple enough to be calculated by small governments and to be understood by the general public and politicians;

- replicable across time, to measure policy effectiveness;

- comparable between governments at the same level (e.g., municipalities), to facilitate policy transfer;

- equity-focused to ensure that women-led, Indigenous households, and other marginalized households receive their fair share;

- evidence-based, as opposed, for instance, to highly politicized social housing waitlists.[38]

One impact of abandoning national leadership on affordable housing three decades ago was that the very definition of affordable housing became fuzzy. The 1944 national advisory committee on postwar reconstruction, known as the Curtis Report, used income category–based measures, a clear definition of affordability (based on proportion of household income), and a housing need assessment method that included both “accumulated needs” and future “needs arising from population growth and [affordable housing] replacement” to recommend that one-third of new construction be non-profit public housing, one-third regulated rental, and one-third private market homeownership.[39] But in the postwar period, the federal government decided to “keep to the marketplace,”[40] with policies to increase homeownership rates that neglected the needs of low-income households.

Austerity-based provincial and municipal affordable housing programs from the late 1980s onwards began to develop new definitions of affordable housing, based on a jurisdiction’s average market rent, a definition that bears no relationship to a household’s ability to pay. This absence of a standardized definition has led to programs like the Rental Construction Finance Initiative, which consumes 40 percent of the National Housing Strategy budget of $70 billion. It requires only 20 percent of subsidized units to be affordable for 10 years, using a unique definition that results in “affordable” rents of more than $2,000 a month for a one-bedroom unit in most Canadian cities,[41] five times the amount a single person on social assistance can afford.

Returning to a nationally mandated needs-based definition of “affordable housing” as meaning “homes that cost no more than 30 percent of low- and moderate-income gross household income” is a vital first step in any rights-based municipal policy. A second step would be regular (e.g., every five years) municipal, provincial/territorial and national housing need assessments that calculate:

- affordable housing deficit by income category, household size, and priority populations;

- ongoing net loss of affordable housing over time;

- population growth and change.[42]

Our Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) project prototyped a standardized need assessment that could be updated every five years with census data (more often at the national level, using Canadian Housing Surveys) and could serve as the basis for future municipal assessments.

Our suggested income categories include:

- Very low income: Households whose income does not exceed 20 percent of Area Median Income (AMI) for a jurisdiction, equivalent to a single person on social assistance: across Canada in 2015, this would have been $15,000 a year or $350 a month maximum housing cost;

- Low income: Households between 21 and 50 percent of AMI, usually equivalent to the income of one full-time minimum wage earner: $35,000 a year or $875 a month maximum housing cost in Canada in 2015;

- Moderate income: 51 to 80 percent of AMI: $55,000 a year or $1,400 a month maximum housing cost in Canada in 2015;

- Average income: 81 to 120 percent of AMI: $85,000 a year or $2,000 a month maximum housing cost in Canada in 2015;

- Higher income: more than 120 percent AMI.

We prototyped these methods with the City of Kelowna, B.C., population 140,000, whose Area Median Income of $71,097 is similar to Canada’s median household income of $70,336. We used social assistance rates for a single person to determine “very low income” and minimum wage for a full-time job to calculate “low income.” After adding 2016 housing need deficit to projected net loss of affordable housing and population growth (based on changes from 2006 to 2016), we calculated the number of new homes that needed to be created from 2016 to 2026 (see Table 1).

Table 1: Projected housing need in units, City of Kelowna to 2026[43]

| Maximum Affordable Monthly Housing Costs | 1 BR | 2 BR | 3 BR | 4+ BR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <$375 | 888 | 105 | 39 | 14 | 1,046 (5.3%) |

| $375–$750 | 3,239 | 1,194 | 332 | 181 | 4,946 (25.4%) |

| $751–$1,375 | 848 | 1,312 | 912 | 774 | 3,846 (19.8%) |

| $1,376–$2,000 | 454 | 643 | 492 | 680 | 2,269 (11.6%) |

| >$2,000 | 327 | 1,189 | 1,647 | 4,204 | 7,367 (37.8%) |

| Total | 5,756 | 4,443 | 3,422 | 5,853 | 19,474 (100%) |

The assessment shows a need for at least 5 percent of new homes created between 2016 and 2026 to cost less than $375 a month, and almost a third to cost less than $750 a month, in order to address core housing need in the City of Kelowna.

The results of the need assessment are in stark contrast to the facts on the ground. With median house prices at more than $1 million and condo prices at $450,000,[44] affordable homeownership is impossible for all but households earning more than 120 percent AMI. Furthermore, the majority of new rental homes in Kelowna are unaffordable to low- and moderate-income households, including those subsidized by federal programs.

Rights-based housing targets that would eliminate homelessness and provide adequate housing for all in Kelowna would be surprisingly close to those targets recommended in 1944:[45] one-third heavily subsidized and ideally non-profit rental homes, with rents no more than $750 a month; one-third rent-regulated homes at between $750 and $2,000 a month; and one-third rental or ownership homes at more than $2,000 a month.

Recommendation: Federal and provincial/territorial governments should implement a needs-based definition of affordable housing to guide their programs and policies. Using that definition, other orders of government, including municipalities, should undertake regular housing need assessments.

Land for non-profit development

From the 1960s until the 1980s, government land and building acquisition was understood to be the best way to provide scaled-up affordable housing. Large projects with up to 50 percent non-profit rental, such as Toronto’s St. Lawrence Neighbourhood, with more than 4,000 homes, were facilitated through land acquisition funded by all three orders of government.[46]

According to a recent study in Metro Vancouver, rental homes that aim to address housing need for very low- and low-income households require free land, construction grants, waivers of development charges and application fees, favourable financing, and ongoing operational support in order to be feasible in the long term. Leasing free government or non-profit land can reduce costs by between 15 and 25 percent, depending on location. The largest potential cost savings, though, come from using a non-profit developer: between 20 and 30 percent of total construction cost[47] (see Table 2).

Table 2: Break Even Rent* calculations, private and non-profit developers, Greater Vancouver[48]

| Capital Cost Scenario** | Private Break Even Rent – 1 BR | Private Break Even Rent – 2 BR | Non-Profit Break Even Rent – 1 BR | Non-Profit Break Even Rent – 2 BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete – No land | $2234 | $2910 | $1539 | $2002 |

| Concerete – Low land | $2418 | $3150 | $1653 | $2151 |

| Concrete – Med land | $2693 | $3509 | $1823 | $2374 |

| Concrete – High land | $2968 | $3868 | $1994 | $2597 |

| Frame – No land | $1941 | $2527 | $1356 | $1765 |

| Frame – Low land | $2124 | $2767 | $1470 | $1913 |

| Frame – Med land | $2400 | $3126 | $1641 | $2136 |

| Frame – High land | $2675 | $3485 | $1812 | $2359 |

**Capital Costs = Construction Cost + Land + Developer’s Profit or Fee. Land cost is set to zero.

Non-profit housing developers also can retain affordable housing through mechanisms such as Community Land Trusts, non-profit organizations that acquire and hold land in perpetuity for affordable housing as a need and not a commodity.[49] Non-profit housing providers can ensure that those in housing need, including those on social housing waiting lists, are prioritized for these homes.

Scaled-up development, which can result in additional savings,[50] requires large non-profit developers working with large sites. This can be accomplished through land readjustment, wherebymunicipalities amass larger sites through agreements with other orders of government or the private sector.[51] Ottawa Community Housing’s plan to construct 1,100 mixed-income affordable rental homes on 15 acres of acquired land was recently expanded by a low-cost sale of six further acres of federal surplus land.[52]

The Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) include a land assessment component. We mapped 230 well-located plots of suitably zoned public and non-profit land that could be used to meet housing need in Kelowna, especially if non-profit developers were favoured.[53]

Recommendation: Municipalities should facilitate free or low-cost provision of suitable land to non-profit developers.

Zoning and approvals

Municipalities play a critical role in housing development by assigning value and regulating use through zoning and approval processes. Land is spatially fixed and a limited resource. Zoning controls the uses of this limited resource, and has been used to exclude people who have less power and wealth from certain areas.

In Toronto, 63.5 percent of residential land is zoned for detached houses that are unaffordable to all but high-income households, although secondary suites and laneway houses have recently been permitted. In Vancouver, the figure is 80.5 percent. In Calgary and Edmonton, the figures are 67.5 percent and 69.3 percent, respectively. Montréal is an outlier, with more than three-quarters of the city’s residents living in duplexes or triplexes, rowhouses, semi-detached houses, or other buildings with fewer than five storeys, more than double the 35 percent figure for Canada as a whole.[54]

Removing exclusionary zoning is now seen as a “necessary, though insufficient, condition for providing adequate housing.”[55] The City of Edmonton (2021) has recently allowed duplexes or triplexes on single detached dwelling lots as a first step in a wholesale revision of its zoning requirements. This review of zoning is informed by a gender and intersectional analysis, including identifying systemic barriers to affordable housing such as restrictions on supportive housing and privileging homeowners over renters. The need to remove minimum parking requirements and expedite “as-of-right” developments without third-party “NIMBY” delays is included in this review, although approving this change is up to the province.[56]

Canadian municipalities can learn from cities around the world. The City of Portland, Oregon, mandates maximum house sizes, and provides density bonuses to non-profit developers (e.g., an as-of-right sixplex rather than a fourplex replacing a single detached house, provided that 50 percent of units are affordable to households earning less than 60 percent of AMI).[57] The City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, mandates 100 percent affordable prices (to median income households or below) for its conversions or demolitions, and has succeeded in steering housing supply in that direction.[58]

Canadian municipalities that have provincial permission to do so are also implementing inclusionary zoning. This mechanism mandates that a proportion of new homes must be social or affordable; it can regulate the required number of bedrooms as well. The City of Montréal’s 20/20/20 bylaw is based on evidence of the required rents and home sizes for households in housing need, mandating 20 percent of new private development in most of the city to be set aside as non-profit, up to 20 percent for regulated rental with an affordability target of 30 percent of moderate-income household rent, and another 20 percent (including the non-profit component) having three or more bedrooms.[59]

Recommendation: Municipalities should remove exclusionary zoning and implement inclusionary zoning, using Portland, Cambridge, and Montréal as examples of best practice. Where necessary, provinces should remove any restrictions, such as required provincial approvals, that municipalities face in implementing these changes.

Preventing the loss of affordable rental housing

Municipalities must also proactively prevent housing loss where they are empowered to do so by provinces. For every one new affordable home with a rent of under $750 a month developed through federal and provincial programs between 2011 and 2016, 15 private-sector rental homes below that price point were lost.[60]

Most mechanisms to prevent affordability loss, including stronger rent control measures such as eliminating vacancy decontrol (resetting rents to market rate once a tenant has moved out), are controlled by provinces. However, British Columbia and Québec have facilitated the municipal acquisition of low-cost rental buildings at risk of being commodified, such as rooming houses.[61] The City of Vancouver and the Province of British Columbia worked together to renovate 13 Single-Room Occupancy hotels purchased from private operators, saving 900 low-income residents from homelessness. These buildings have now been turned over to non-profit housing providers, with an ongoing maintenance agreement that will keep rents low and homes repaired.[62]

Most mechanisms to prevent affordability loss, including stronger rent control measures such as eliminating vacancy decontrol (resetting rents to market rate once a tenant has moved out), are controlled by provinces.

Several B.C. municipalities, including the City of Burnaby, have introduced rental-only zoning, after this power was allowed by the province. This is an overlay protecting existing affordable rental buildings (private and non-profit) from conversion to condominium tenure. In addition, tenants evicted because of repairs to older buildings or demolition must be offered an equivalently sized unit for the equivalent rent in the renovated or new building. An inclusionary zoning overlay of 20 percent rental is required in all new developments.[63]

Recommendation: Provincial and municipal governments should implement policies to retain affordable housing, including rent controls, the elimination of vacancy decontrol, and rental-only zoning. They should share data and resources in order to purchase rental housing at risk of becoming unaffordable.

Conclusion: Multi-level governance for affordable housing

All three recommended mechanisms to scale up and maintain affordable housing – using government land for non-profit housing, reforming exclusionary zoning, and retaining affordable rental – require approvals from provinces and territories, and new low-cost rental housing requires infrastructure funding from the federal government. (See Lilian Chau and Jill Atkey’s paper for an example of the important role of provincial and federal funding for affordable rental housing.)

A recent review of the National Housing Strategy from a human rights perspective noted that the affordable housing and homelessness crisis requires an “all-hands-on-deck” approach, including federal taxation reform to limit housing speculation, conditions to provincial transfers that include rent control reform, and direct financing to municipalities.[64]

Affordable housing cannot be developed or maintained without coordinated leadership from all three orders of government. The federal government has access to the biggest infrastructure finance and investment levers and should be providing national leadership when it comes to multi-scale governance, including targets, consistent definitions, and need assessment methods. The provincial government has the biggest regulatory levers to keep private market rental affordable, including landlord-tenant laws and permitting major changes in land use planning and zoning. It is also responsible for setting social assistance rates and minimum wages, determinants of low-income households’ ability to pay rent. Provinces and territories also legislate the powers of local government to regulate appropriately to meet targets, for instance, the “right of first refusal” to purchase at-risk private affordable housing, or regulating rents.

Given high housing prices in many city-regions, Canada’s huge affordable housing deficit will not be addressed without relying on scaled-up and regulated rental housing. Here, municipalities play a critical role. Municipalities can, with senior government assistance, acquire land for non-profit development, expedite approvals for non-profit and affordable housing, and defer or eliminate development charges and property taxes for housing renting below a certain amount. Construction finance and operational subsidies should not be the responsibility of underfunded municipalities.

Local governments can zone to vastly increase the amount of available land for higher-density rental, but they cannot regulate affordable rents without provincial tools. They can prevent the loss of affordable rental housing only if they have provincial permission to do so and acquire properties for long-term secure rental by non-profits only with expanded funds provided as part of the National Housing Strategy. For the right to housing to be realized, senior governments must provide municipalities with the powers and infrastructure funding they need to fulfil their role.

3. Non-Profit Rental Housing: Streamline Approvals Process to Accelerate Construction

By Lilian Chau and Jill Atkey

Lilian Chau is CEO of Entre Nous Femmes Housing Society in Vancouver.

Jill Atkey is CEO of British Columbia Non-Profit Housing Association.

Introduction

Most regions of the country are experiencing housing affordability challenges. It would be fair to characterize the situation in many urban centres as a crisis of affordability for those trying to enter the homeownership market and those renting their homes on local incomes.

How we arrived at this crisis in Canada has been covered previously in this report. When it comes to rental housing, the ending of rental tax incentive programs in the early 1980s, the discontinuation of affordable housing programs in the early 1990s, and in some provinces, the introduction of legislation allowing for condominium ownership, which enabled quicker and more significant returns for private-sector developers, all reduced rental supply. Coupled with increased demand through the 2000s due to population growth and the tendency for individuals and families to stay in rentals longer as they were priced out of homeownership, the conditions for a rental supply crisis were complete.

Many of policy choices and market forces are beyond the control of municipalities. Nevertheless, cities face increasing pressure from advocates, policy experts, and senior orders of government to help ensure an adequate housing supply.

Finally, the introduction of Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) in Canada in 2008, which many saw as a hopeful indicator of a renewed interest in rental buildings, poses a significant risk to the existing rental supply. Multi-family buildings are now being sold to the highest bidder with the expectation of healthy returns on investment, made possible only by driving rents higher in anticipation that rental supply will remain constricted in large and mid-sized urban centres well into the future.

Many of these policy choices and market forces are beyond the control of municipalities. Nevertheless, cities face increasing pressure from advocates, policy experts, and senior orders of government to help ensure an adequate housing supply. This paper examines the roles cities can play in ensuring sufficient supply and affordability of new rental homes, drawing in particular on the British Columbia experience with community housing.

We will outline how municipalities can use zoning, efficient processes, direct funding, and incentives to improve the feasibility of not-for-profit housing projects and can facilitate access to provincial and federal housing funding programs. In addition, we will show how senior orders of government can play a crucial role through direct investment in housing and a strong and streamlined regulatory environment in which municipalities can more easily and quickly approve a greater supply of non-market housing.

Municipal tools to accelerate the production of affordable housing

Whether a not-for-profit or a market developer leads a rental development, the municipal approvals process is essentially the same, and it is an increasingly complex and costly process. Once a project enters the process, it is sensitive to three critical risks: time, costs, and certainty of approvals. The longer the process takes, the greater the costs and uncertainty for a project; the higher the costs, the fewer opportunities to create greater affordability and make the project financially feasible; the more uncertainty created by vocal opponents and unpredictable Council decisions, the less chance the project will be built.

While both non-market and market developers face the same municipal regulatory challenges, the impacts are more acute for the not-for-profit and co-op housing sectors, given their limited ability to access additional capital and equity to invest in a project. Any additional costs are added to the project’s break-even rents, limiting the project’s ability to increase the level of affordability and the number of affordable homes and impacting financial viability.

Municipalities can implement different tools to enable the success of affordable housing projects in their communities if they choose to. This section will explore how municipalities in British Columbia are accelerating the production of affordable housing in three ways:

- reducing the capital and operating costs of a project;

- getting projects off the ground faster;

- creating greater certainty around approvals.

Reducing capital and operating costs

Providing deeply affordable rents at a 50 to 90 percent discount relative to market rents is the goal for most not-for-profits serving households that rely on income assistance or government subsidies, or that have incomes that fall below $46,000, the median income for renter households in British Columbia. Importantly, however, most new developments follow a mixed-income model and are a key part of the solution to many municipalities’ workforce housing crises.

With rising construction costs and increasing layers of requirements from funders, lenders, and municipalities, organizations must try to reduce costs, balance their budgets, and seek funding from different sources. Municipal contributions such as grants, permit and fee waivers, and property tax exemptions or deferrals are critical to offsetting capital and long-term operating costs, increasing affordability, and enabling projects to leverage necessary contributions from other funders and senior orders of government.

Direct grant contributions

Some municipalities in British Columbia, such as Kelowna, Burnaby, Richmond, Vancouver, and North Vancouver, have created direct capital grant contributions to affordable housing projects through Housing Reserve Funds collected through fees, levies, and community amenity contributions. Grants are usually provided based on the number of affordable units and the unit size and require the registration of a Housing Agreement guaranteeing rent levels and the number of units for a specified length of time. To benefit affordable housing projects by not-for-profit organizations, future funding programs should have quick approval times and clear and straightforward funding calculations that do not require significant resources from the not-for-profit or City staff to submit and review applications.

Fee waivers

A significant portion of a project’s soft costs can be saved by waiving or offsetting municipal permit fees and development cost charges. For example, a development cost charge waiver on a 100-unit affordable rental project in Vancouver provides almost $2 million in cost savings. If rezoning, development permit, and building permit fees are waived for the same project, this would save the project an additional $275,000. While Vancouver, Vernon, and Nanaimo have chosen to waive development cost charges for not-for-profit projects altogether, other municipalities, like Kelowna, Richmond, and Surrey, provide a grant to the project from their Housing Reserve Funds to offset development cost charges and permit fees charged to the project. In this way, the municipality still extracts the exact costs from all developers, and affordable housing projects receive an additional grant to offset the costs.

It is important to note that the Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation’s (CMHC) Co-Investment Fund, a federal affordable housing funding program, considers municipal development cost charges waivers a minimum requirement for governments to be considered a “co-investor” on a project, thus making the project eligible for federal funding.

Property tax exemptions

Besides upfront capital costs, long-term expenses such as property taxes can significantly impact financial viability. Property tax exemptions are particularly important for projects that do not have an ongoing government subsidy. In some jurisdictions, property taxes can be as much as 20 percent of a project’s annual operating expenses. Without the burden of needing to generate enough rental income to cover property tax expenses, the project can charge lower rents that are affordable to lower household incomes and can turn market units into non-market homes. Property tax exemptions significantly benefit affordable housing projects in municipalities with high land prices and without ongoing government subsidies to help reduce long-term operating costs.

Victoria and Langford on Vancouver Island offer a 100 percent permissive tax exemption to not-for-profit affordable housing projects for 10 years. While it is not a property tax exemption for the life of the building, the costs savings still enable projects in those municipalities to stabilize rents, maintain greater levels of affordability, and reduce the project’s overall debt load over those 10 years.

Table 3 shows how a property tax exemption can significantly affect affordability. The project is a recently approved, 157-unit affordable seniors’ rental building in Vancouver. The project successfully received federal funding and financing and has no ongoing government subsidy, which means the building’s rental income must cover all debt and operating expenses. A property tax exemption would have allowed the project to double the number of below-market rental units from 57 to 105.

Table 3: Effects of a property tax exemption on an affordable housing project

| Property Taxes vs. Affordability | Property Tax | Property Tax Exemption |

|---|---|---|

| Property taxes per year | $162,331 | $0 |

| Per Unit Per Month operating expense (PUPM) | $386.22 | $300.06 |

| Total number of units | 157 | 157 |

| Deeply affordable rents $803 | 57 | 70 |

| Below market rents $1,250 – $1,437 | 0 | 35 |

| Market rents $1,607 – $1,869 | 100 | 52 |

| Percentage of below market unit | 36% | 67% |

Getting projects off the ground faster

Because the rezoning and development permit process can be long and drawn out, it may add to development costs. An extended approvals timeline may cause an affordable housing project to delay financing, miss a funding deadline, or lose an opportunity to lock in a lower interest rate, adding to costs and creating uncertainty. Municipalities in British Columbia have recognized the impacts of long approval processes. Many are fast-tracking affordable housing projects by reorganizing their planning teams and streamlining complex review processes.

Burnaby’s Preferential Processing policy for affordable housing applications aims to shorten the timeframe for rezoning approvals to six months. Burnaby’s goal is to assist affordable housing developers to meet senior government funding deadlines as part of the expedited process. Similarly, Vancouver’s Social Housing or Rental Tenure (SHORT) Program seeks to reduce development approval times by 50 percent by providing rezoning approvals in 28 weeks and development permit approval in 12 weeks. Exempting affordable housing projects from review by urban design panels and committees, as is done in Vernon, is another way to reduce processing and approval times.

Providing greater certainty

Affordable housing developments often seek higher densities that require rezoning in most municipalities. With the rezoning process comes the risks of contentious public hearings and the loss of Council support. To increase the likelihood of affordable housing projects getting approved, a handful of cities in British Columbia are looking at ways to lead the rezoning process themselves by up-zoning pieces of land or properties, changing zoning bylaws to allow higher-density projects to go straight to a development permit, and waiving public hearings in the rezoning for affordable housing projects.

The pace of change in municipal approaches has been slow, leading to increasing calls for the province to regulate minimum-density thresholds, as other jurisdictions have done. (Whitzman et al. discuss the challenge of exclusionary zoning in their paper earlier in this report.)

In 2016, the City of North Vancouver ambitiously moved to rezone an area with 300 single detached homes to create a new mixed-use, multi-family neighbourhood for 2,000 homes in the Moodyville neighbourhood. The area-wide rezoning, new zoning designations, and design guidelines were intended to increase certainty for owners, neighbours, and developers. While this zoning was not intended specifically to accommodate affordable housing, the example shows how a City-led process can help rally community support and create a greater diversity of housing in low-density neighbourhoods within a short period.

Vancouver Council recently approved an increase to the permitted density and heights in certain parts of the City to allow not-for-profit landowners to build up to six storeys with a development permit. This change would eliminate at least 12 months of rezoning approval time and costs and make it more financially feasible for not-for-profits to redevelop more homes.

Intergovernmental support for municipalities

It is clear from the preceding discussion that municipalities are essential partners in the community housing sector in improving the affordability of community housing projects, not just for the residents who move in when the building opens, but for the generations of people who will find their homes there during the building’s lifespan. However, municipalities and not-for-profits cannot do this work alone. Senior orders of government also have a responsibility to invest their capital in community housing and streamline the complex cross-jurisdictional permitting processes that can slow down the creation of affordable housing.

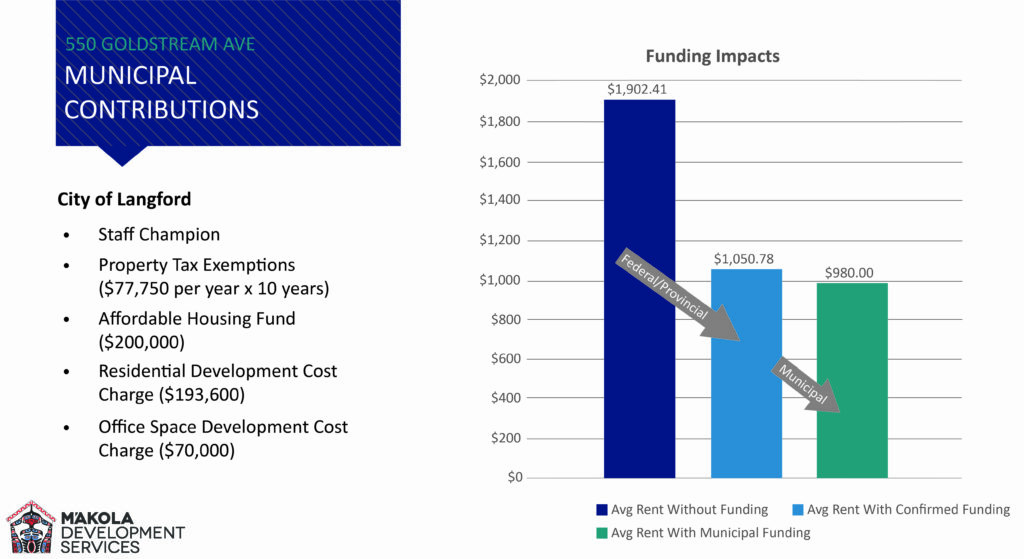

As we see with the Langford example, the most considerable contributions to affordability came from federal and provincial funding programs, taking the break-even rents from being affordable to households earning $76,000 annually to households earning $42,000, just above the median income for a renter household in Canada. Langford’s contribution enabled the not-for-profit to access funding from senior orders of government and resulted in even further rent reductions.

Case Study: M’akola Development Services in the City of Langford

A recent affordable rental project by M’akola Development Services in the City of Langford illustrates how municipal contributions can directly impact affordability when layered with senior government funding. The governments of Canada and British Columbia provided combined investments of nearly $4.9 million through the Affordable Rental Housing Initiative under the Canada-B.C. Agreement for Investment in Affordable Housing. Further, the B.C. government provided almost $6.3 million in construction financing.

As part of Langford’s affordable housing program, the City provided a 10-year property tax exemption, development cost charge waivers, and a $463,600 grant from the Affordable Housing Fund to reduce development costs, along with $777,500 in property tax savings over 10 years. A total of $1.2 million in municipal contributions enabled the project to reduce rents from $1,050 a month for people with low to moderate incomes to $980, which allows seniors on fixed incomes, and households earning less than the median income of $40,000 a year in Langford (such as single-parent households) to afford a home.

Provincial investments and interventions

While municipalities are vital actors in housing policy, the provinces have important roles to play in ensuring key housing targets are met. British Columbia has required each municipality to develop a housing need and demand study and made funding available for these studies. (For more on the importance of regularly assessing housing need, see Whitzman et al.’s paper.) The requirement was a step in the right direction, but there remains no requirement for cities to zone for and approve the housing their studies indicate is needed. No legislation exists to ensure that municipalities zone sufficiently to meet demand or approve additional housing supply in a timely manner.

The Canada-B.C. Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability recommended several actions provinces can take to ensure municipalities are approving a sufficient supply of housing to meet demand. Implementing legislation requiring cities to zone for and approve the housing supply identified in their need and demand studies would also help address the lack of regional coordination on housing plans. Jurisdictions such as California, Oregon, and New Zealand, among others, have explored and in some cases passed legislation ending single-family zoning in major urban centres. Provinces in Canada with large urban centres and affordable housing pressures should consider similar actions.

Further, to ensure municipalities are responding to the housing needs in their community, provinces can streamline regulatory processes and create funding programs to incentivize the creation of community housing. They can remove regulations that stand in the way of municipal action. In a complex, cross-jurisdictional environment, the potential for policy incoherence is strong and requires expertise and time to navigate.[65]

Recently, for instance, British Columbia moved to streamline the development process even further by no longer requiring municipal governments to conduct public hearings for rezoning applications if the proposed changes align with the City’s approved Official Community Plan. This was the result of recommendations from the 2019 Development Approvals Process Review, which indicated that public hearings were not providing meaningful feedback.[66] If Councils exercise this option, it will significantly reduce development times and costs.

In addition to municipal development requirements, a project seeking approval in British Columbia may also be subject to regulations that touch the following provincial ministries and crown corporations: Ministry of Environment and Climate Strategy; Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development; Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure; and B.C. Hydro. While the regulations themselves may be necessary and even desirable, more coordination between ministries is required to reduce the incoherence of varying requirements and streamline the approvals process.

Federal investments and interventions

To increase community housing supply, the federal government should return to the funding levels consistent through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, when 10 percent of all new housing was not-for-profit and co-op housing. As Steve Pomeroy has noted, the majority of spending under the National Housing Strategy has been in the form of low-cost financing for primarily market rental buildings.[67] Market supply is necessary, and the government has a role in incentivizing it, but it does not align with the National Housing Strategy goals, which prioritize housing for low-income and systemically marginalized households.

Much has changed during the federal government’s 25-year absence from the housing scene, including the creation of vital housing programs in some provinces. In those provinces, strong federal-provincial cooperation is necessary. It could take the form of bilateral agreements that include funds from National Housing Strategy programs for the provinces to deploy alongside their own programs, which would benefit from increasing uptake of federal funding programs that are currently underused.

With the support of municipal and senior government partners, the community housing sector can deliver the right supply, lock in affordability, and meet a broad range of housing needs.

The federal government could also make its programs more flexible by deferring to provincial building codes to reduce the policy inconsistencies that non-profits must navigate. Furthermore, basing underwriting requirements on not-for-profit conditions rather than market rental housing, like the National Housing Co-Investment Fund, would allow greater flexibility and funding certainty as projects manoeuvre their way through the municipal approval process. These changes would provide additional clarity for non-profit developers, the municipality, and community stakeholders.

Conclusion

A renewed interest in affordable housing at all orders of government means that there are more opportunities to create affordable rental housing for working professionals, people with low incomes, and those who cannot find adequate housing in the private market. Municipalities can play a critical role in ensuring the right supply is built and contribute to the affordability of new developments through direct contributions, speeding up the approvals process, and creating greater certainty for approvals. With the support of municipal and senior government partners, the community housing sector can deliver the right supply, lock in affordability, and meet a broad range of housing needs. With a concerted commitment to change what is not working, we can start to turn a corner on the affordable housing crisis and ultimately ensure that everyone has a safe, secure, and affordable place to call home.

4. Social Housing: Strong City Roles Need Regional and Federal-Provincial Partnerships

By Greg Suttor

Greg Suttor is the author of Still Renovating: A History of Canadian Social Housing Policy (2016).

Introduction

Since the late 2010s, resurgent rental demand, tight markets, and escalating affordability problems have put social or community housing back on the policy agenda. Many Canadian municipalities are taking stronger action on rental housing; the National Housing Strategy (NHS) brings renewed federal priority; and some NHS programs look to cities as partners.[68] (See Chau and Atkey for more on affordable rental housing.)

What should be the role of cities in social housing? The challenge in Canada today is to capitalize on strong local priorities, while pursuing broader goals of rebuilding federal-provincial partnerships and pursuing regional approaches. Municipal governments have strong capacity in establishing strategies suited to local needs and opportunities, delivering programs, developing and operating housing, and collaborating with non-profits. The provincial role in social housing is vital because of provinces’ greater fiscal capacity, the many links between housing and redistributive social programs as well as health, and the need for action at the city-region scale.

This paper uses the term social housing (also called community housing) to include public, municipal, non-profit, and co-operative housing. This includes post-2000 “affordable” housing with moderate market rents, which have many precedents in earlier programs.[69] It includes programs that create and sustain that housing stock, and related programs that make rents affordable.[70]

The challenge in Canada today is to capitalize on strong local priorities, while pursuing broader goals of rebuilding federal-provincial partnerships and pursuing regional approaches.

Canadian and international experience shows wide variation and little standard wisdom on cities’ role. The municipal role is large and rising in the United States, modest but rising in France, sidelined and constrained in the United Kingdom, and small in Australia.[71] Local roles range from very limited in some provinces and cities, to very strong with active provincial support in British Columbia and Québec,[72] to Ontario municipalities running programs that are provincial elsewhere. Municipal funding ranges from tax exemptions for new projects in some places, to $1 billion in annual ongoing funding in Ontario.[73]

Housing is local, but also much broader

A discussion of cities’ role in social housing must consider housing markets – the context in which needs arise and policy and program responses happen. We must also consider the linkages to related policy spheres, above all to social programs and to urban development.

In social policy, if we look through the lens of production and stock, social housing is part of social infrastructure, with profound impacts on health, well-being, and child development.[74] From this perspective, housing, although not strictly a public good, is akin to child care or schools. If we want healthy communities with moderate-rent housing, or with homes for people with low incomes, disabilities, or other disadvantages, then social housing is part of the required infrastructure.

If we view things through the lens of affordability, then social housing is closely tied to incomes policy – such as wage laws, tax benefits, pensions, and social assistance – that mitigate economic inequalities in our society. Housing for people who are homeless or have disabilities also has a close link to social programs, through health or social service funding for support staff.

In urban development, federal policy – tax law, mortgage lending rules, and interest rates – fundamentally structures the housing market. Provincial as well as local decisions on highways, major transit lines, trunk sewers, water mains, and growth boundaries shape the spatial extent of local markets. Scarce rental supply, unaffordable rents, neighbourhood decline, and social segregation – issues we expect social housing to address – arise in the wake of housing demand dominated by upper-income groups, facilitated by these larger housing-related policy spheres.

Let us dispense with the notion that housing is primarily “local.” Of course market conditions are area-specific, and housing is situated in distinct places, shaped by local built legacies, and tied to local social profiles. But job growth, demographics, immigrant arrivals, capital flows, and income disparities, which feed housing demand and housing needs, arise on a national scale or from a city-region’s place in the national economy. Housing is huge economically, at about 20 percent of GDP.[75] So housing is not primarily local in a policy sense, any more than schools or jobs are.

Housing markets do not stop at municipal boundaries; their main geography is the city-region (or metropolitan area), such as Greater Victoria or Greater Montréal. Most large city-regions consist of multiple municipalities with no joint governance.[76] In such cases, no local authority can gauge or address issues comprehensively across the local housing market. So in considering the role of cities, we must look not only at municipalities but also at the city-region.[77]

Social housing policy is not just about building and running projects. It is about broad matters: mortgage financing; access rules and priorities; rent subsidies, whether project-based (rent geared to income) or portable (housing benefits/allowances); balancing supply and demand; aligning funding for support services; adapting social housing assets and financial flows to help create new housing; and doing this in ways that are equitable across a city-region and between them. Municipalities can do only some of these things.

These linked policy spheres are primarily federal and provincial. They entail large and costly programs; they involve broad tax and infrastructure policy; they cross municipal boundaries; they are important to the economy; and they are redistributive. Social housing is a sphere of modest scale, at the edges of big federal and provincial policy domains. There is no reasonable basis to carve it off and deem it to be “local.”

Yet housing is also local and city-regional. Building it involves local land use decisions and related politics. Housing needs manifest locally as low-quality apartments, room renting, overcrowding, food bank use, spatial divides between affluent and poor households, and homelessness. Attaining the goals of socially mixed and transit-supportive communities hinges on decisions about denser housing, including rental. Social housing is entwined with central-city renewal, inner-suburban decline, and outer-suburban expansion.

Intergovernmental perspectives

Housing is conventionally said to fall under the provincial responsibility for “property and civil rights.” But in practice, housing policy, including social housing, is neither explicitly a federal or a provincial responsibility, nor an explicitly shared responsibility,[78] but a matter of ambiguous jurisdiction and complex politics. Federal spending power and federal mortgage lending has shaped the system for many years; cost-sharing is pervasive; what the provinces dominate is program delivery.[79] The municipal role is large, but shaped by senior government funding and provincial policy on municipal fiscal and other powers. Canada has had seven decades of constitutional practice in social housing on this basis.

This multi-scalar reality[80] points to the need for intergovernmental collaboration. Because social housing can help address market dysfunctions, and is part of social infrastructure and income-related programs, it requires a strong federal and provincial policy role. Because building housing and subsidizing rents are so expensive, they require that federal and provincial funds pay most of the costs. Yet most delivery is best done locally. Local decisions can calibrate delivery to needs on the ground – including those of seniors, homeless people, working-poor families, new immigrants, or people with disabilities – or to shortfalls of rental housing. Local decisions determine whether urban design and community mix in built form, tenure, and income will succeed or fail.

Internationally, successful social housing systems have seen national or provincial/state governments frame policy and provide most funding, with municipalities active in development and in owning and running housing. This was the case in the heyday of social housing in leading European countries,[81] and in Canada too. In the early postwar years (1949 to mid-1960s), most public housing was municipally owned but created and funded under federal programs. In the next decade (mid-1960s to mid-1970s), the pitfalls of oversized public housing projects with little income mix arose partly from not enough local say. Through the two decades of strong non-profit and co-op production (mid-1970s to early 1990s), a federal-provincial partnership set policy and funded projects, but local and metro municipal housing corporations carried out one-third of production and supported non-profit projects.[82]

Devolution has been widespread across affluent nations since the 1980s, but Canada is an extreme. In Europe, devolution reflected the principle of subsidiarity – the principle of putting policy responsibilities at the most local scale feasible to foster democratic responsiveness – and similar arguments are made in the U.S. context.[83] But federalism can also mean sloughing off responsibilities to other orders of government[84] and devolution can be entwined with retrenchment: scaling back the role of the state and handing responsibilities to government with lower levels of fiscal and policy capacity.[85] In Canada, the two decades starting in the mid-1990s were dominated by devolution and its aftermath, profoundly tied to retrenchment. Federal withdrawal from social housing was part of a broad downsizing of social programs. Ontario’s devolution to municipalities was a means to remove the province from that policy sphere.[86]

A stronger federal-provincial partnership can enable more social housing overall and more municipal action in general.

Local responsibility poses risks in the mismatch of boundaries to housing markets. Much Canadian social housing production in the 1960s to 1980s was spread across the city-region, and low-income renters lived in many of the same neighbourhoods as middle-income households.[87] This contrasted with the situation in the United States, where almost all public housing was built in central cities[88] – reinforcing a city/suburban social and racial divide, and confirming the suburbs as places where affluent people could opt out of urban issues.[89]

Today, affordable housing is a higher priority in the municipalities of Montréal, Toronto, and Vancouver – which constitute the central 30 to 40 percent of their respective city-regions, and have complex social needs and more “urban” politics – than in the middle and outer suburbs where most people live and pay taxes. Building most social housing downtown or in inner suburbs where renters live can reinforce poverty concentrations and neighbourhood social divides, while ignoring severe shortfalls of rental housing in outer suburban job growth zones.

We face a political conundrum – of strong municipal political priority versus weak fiscal capacity and constrained geography. The rising policy priority and funding for social housing in big cities in recent years is striking[90] and valuable. Municipal capacity and expertise are high in matters such as setting local strategies, providing local funding, allocating federal-provincial funding, working with non-profits, and delivering programs. While arguing for a strong federal-provincial role, we should leverage and not undermine local capacity and priority.

Some suggestions for the municipal and city-region role in social housing

Canadian social housing is at a different place in the early 2020s from where it was a decade or two ago. Big-city priority and capacity is far higher. There is renewed federal leadership through the National Housing Strategy.[91] Yet it remains a weaker federal-provincial partnership than in the 20th century – in the scale of cost-shared programs and the separation of federally led new supply from large provincial social housing systems.

Excepting program initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall scale of federal funding has changed little.[92] Canada remains a low-spending jurisdiction on housing subsidy by OECD norms.[93] In Ontario there is no rollback of municipal devolution to restore full provincial funding and strategic leadership. There is huge variation among provinces, within city-regions, and among municipalities in the city role in framing policy, funding, delivering programs, and developing and owning housing.

These observations are jumping-off points for some suggested policy directions for cities’ role in social housing today.

Support cities through a stronger federal-provincial partnership

A stronger federal-provincial partnership can enable more social housing overall and more municipal action in general. This would involve steps such as re-establishing structured cost-sharing formulas for new social and affordable housing, expanding the system at least commensurately with population growth, and moving toward integrating rent-geared-to-income units with portable rent subsidies. Targeted federal partnerships with big-city municipalities can be useful,[94] but these will not achieve these broader objectives, will not foster social integration across city-regions, and will tend to fragment an already weak system.

Use federal-provincial funding to support local delivery

Most capital and operating funding for social housing should be federal and provincial, for reasons of equity, fiscal capacity, and policy linkages.[95] Funding should support local development, ownership, and operation, and some local program administration. For Ontario, with 40 percent of Canadian social housing, this principle requires uploading from the municipal to provincial order the responsibility to fund ongoing housing subsidy, consistent with practice in other provinces and around the world. (Program rules and reporting – as in public health, child care, etc. – can ensure that local delivery is accountable.)

Retain local or city-region development, ownership, and operation of social housing

Local development, ownership, and operation (with federal-provincial funding) is prevalent for the half of Canadian social housing that is publicly owned. This is the best approach (with possible exceptions in some smaller provinces), as it enables integration of affordable housing with other development planning and with the local community context.

Use and support the capacity of big cities in delivery

Large and mid-sized urban municipalities have high capacity in setting local strategies, allocating combined federal-provincial-local funding, working with non-profits, integrating housing and homelessness initiatives, and delivering programs. Provincial administration of cost-shared programs, and federal housing partnerships with municipalities should draw on and reinforce this expertise.

Foster city-region approaches

Developing affordable rental housing across the city-region is important for social mix, fiscal equity, and locating housing near jobs. A focus on big-city municipalities misses this broad picture in multi-municipal city-regions. Approaches may include:

- regional and suburban non-profits;

- regional fiscal equalization of housing funding[96];

- ample allocations to suburban non-profits and municipalities;

- city-region rental strategies;

- regional housing development corporations.

Many of these approaches will require provincial leadership.

Make funding conditional on and supportive of local strategies

A vital way to ensure that federal-provincial funding and broad priorities work effectively with local delivery is to “fund the plan.” This means funding the implementation of municipal or city-region multi-year plans that embody local priorities accepted by federal and provincial funders. (It is not about dollars for planning processes.) This approach is used in federal homelessness funding and other spheres. It aligns resources with priorities that respond to local conditions, and is a framework for accountability.

Enhance the fiscal capacity of municipal and city-region governments

The social and political realities of big-city municipalities create a priority for affordable housing that is often stronger than at the other orders of government. These cities require the fiscal capacity to implement these priorities and to stretch federal-provincial funding further in markets with higher costs and higher needs. Steps to enhance the fiscal capacity of municipalities through new revenue sources[97] will serve housing priorities alongside other urban needs.

5. Homelessness: Increase Investment in Municipally Led Programs

By Nick Falvo

Nick Falvo is a Calgary-based research consultant with a PhD in Public Policy.

Introduction

Canadian municipalities play very important roles – albeit varied ones – with respect to homelessness. These roles pertain to land-use planning, bylaw creation and enforcement, local service coordination, the ownership of land and facilities, and oversight of public services. The municipal role also includes the ability to deploy municipal staff, advocate, undertake analysis, and facilitate training.

This essay provides an overview of all these roles, as well as broad recommendations in terms of what needs to change for municipalities to contribute even more to addressing homelessness.

The unique role of municipalities vis-à-vis homelessness

Canadian municipalities can play meaningful roles in both preventing and addressing homelessness. Admittedly, some municipalities have larger mandates due to provincial devolution of responsibilities, while some choose to play greater roles than others. The backgrounder at the start of this report briefly noted how municipalities are involved in housing policy. This section expands on these roles in relation to homelessness.

Land-use planning

All provinces and territories have enacted legislation, such as municipal acts and planning acts, that effectively devolve responsibility for planning to municipal governments, while setting guidelines and restrictions as to what municipalities can do. This is relevant to both the creation and day-to-day operation of emergency shelters, daytime facilities for persons experiencing homelessness (sometimes known as drop-ins or day centres), and various types of housing (including supportive housing). Municipal governments decide which areas of their municipality can be zoned for what purposes, how the public is to be engaged in considering projects, how quickly approvals can happen, and which proposals to approve.

Bylaw creation and enforcement

Municipal governments enact and enforce bylaws relevant to panhandling and outdoor sleeping. The nature of these laws depends on enabling legislation passed by provincial or territorial governments. Bylaws also have important implications for outdoor sleeping, including encampment management (encampments come with fire-related risks, such as open flames, unsafe wiring, and gasoline and propane storage).

Coordination of local responses

Homelessness takes unique forms in different municipalities. Factors that vary across municipalities include: