Executive Summary

The Government of Canada recognizes that Canadian society is aging,[1] noting that approximately 25 percent of Canadians will be over the age of 65 by 2036.[2] Responsibility for attending to the challenges this trend poses falls to different orders of government, according to their jurisdiction.

Provincial governments have a constitutional responsibility for institutions such as hospitals and long-term care facilities that deliver care for seniors, and benefit from significant federal transfers that provide funding for the services these institutions support.

In Ontario, municipalities have responsibilities at two levels: as service managers responsible for providing at least one long-term care home; and, as the order of government responsible for urban planning, for building age-friendly communities. The latter role recognizes that the care of people who are seniors goes far beyond providing hospitals and long-term care facilities to creating urban environments and community-based services that meet their needs.

The three papers in this report examine the role that Canadian municipalities currently play in long-term care, with a focus on Ontario, and how other orders of government can support that role. The papers also propose policies to strengthen the municipal role while improving the quality of care, integrating health services, and enhancing the livability of communities.

Municipalities

Pat Armstrong focusses on the nature of long-term care facilities operated by municipalities, emphasizing the high quality of care they provide relative to private and for-profit homes.

Daniella Balasal and Nadia De Santi introduce the concept of age-friendly communities, describing how municipalities are developing strategies and plans to meet the needs of their aging populations outside institutional settings.

Shirley Hoy situates municipalities as the “public eye” on the long-term care system, explaining that because they are directly involved in running long-term care homes, municipal staff offer leadership in the sector, demonstrating best practices that spill over to private and non-profit providers.

Provincial governments

Armstrong sets out Ontario’s specific role with respect to funding and regulating municipal long-term care homes. She calls for this responsibility to be strengthened, with particular attention to funding for improved wages for workers in long-term care facilities.

Balasal and De Santi cite Ontario’s age-friendly community planning guide as an overarching framework for municipalities to use to develop local strategies and plans. By providing guidance, the Province, as the level of government with responsibility for municipalities, facilitates local initiatives.

Hoy examines Ontario’s role in long-term care in the context of the broader elder care system. She notes that provincial health services, such as doctors and hospitals, should be fully integrated with long-term care homes and community-based care for seniors.

While these papers focus on Ontario practices, there are lessons to be shared with all provinces and territories.

Federal government

Armstrong suggests that the federal government should apply conditions to transfer payments to encourage other orders of government to adopt higher standards of quality for long-term care homes.

Balasal and De Santi trace the conceptual origins of age-friendly communities to international conferences that brought together national governments. Subsequently, the work undertaken at the international level filtered down to inform local initiatives. More specifically, they note how federal initiatives, like the New Horizons for Seniors grant program, are supporting age-friendly communities.

Hoy regards the 2023 health care funding deal between the federal government and the provinces as the impetus for strengthening long-term care at the local level. In her view, the agreement provides an opportunity to invest in new and better ways of doing things within the elder care system.

Intergovernmental cooperation

Contributors call for greater vertical and horizontal cooperation. Vertical cooperation could help to universalize standards, particularly where, as Armstrong describes, a higher order of government could require municipalities to implement certain quality standards through its funding contributions. Horizontal cooperation could better integrate hospital, long-term care, and community services to support seniors as they move in and out of residential settings – what Hoy describes as the “campus of care” model.

Backgrounder: Municipalities and Long-Term Care

By Gabriel Eidelman, Spencer Neufeld, and Kass Forman

Gabriel Eidelman is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, and Director of the Urban Policy Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Spencer Neufeld is a recent Master of Public Policy graduate from the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Kass Forman is the former Manager, Programs and Research at the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

Long-term care refers to care for individuals with chronic health conditions, disabilities, or mental health issues who cannot fully care for themselves and require personal, social, nursing, or medical services over extended periods of time. Mainly concentrated on seniors, these services are provided either formally by professional nurses or personal support workers, or more commonly, informally by family members, friends, or community members in a variety of settings. Together, these services comprise a broader “continuum of care,” from around-the-clock care offered in dedicated long-term facilities to home-based services for people capable of living independently.[3]

Although not all residents of long-term care facilities are seniors, a large share of long-term care services are geared toward this population. More than seven million Canadians are currently 65 or older, a number expected to grow substantially as the baby-boomer generation ages.[4] Of this total, approximately 400,000 seniors reside in some form of congregate dwelling.[5] Roughly half of this population live in long-term care facilities, which provide 24-hour care and receive full or partial government funding.

Long-term care facilities go by many names, including long-term care homes, nursing homes, personal care homes, assisted living or supportive care facilities, and continuing care residences.[6] As of 2021, there were about 2,000 long-term care facilities in Canada, with permanent capacity of nearly 200,000 beds – or 29 beds per 1,000 people 65 or older.[7] Nearly half (46 percent) of these facilities are publicly owned, with the remainder owned by private for-profit (29 percent) and non-profit (23 percent) organizations.[8] The primary role of government in Canada’s system is to provide and oversee long-term care facilities and, to a lesser extent, community-based recreational or social services for seniors and individuals living with long-term disabilities. In Ontario, municipal governments have a role in delivering long-term care that is more pronounced than in other provinces. This is owing to the requirement, particular to Ontario, that each single- and upper-tier municipality (outside the northern part of the province) maintain at least one long-term care home.[9] Such local involvement has its origins in 19th century statutes that required houses of industry be established for “the indigent” in each district of the province. By the 1940s, this legislation had evolved into a provincial requirement that municipalities establish “homes for the aged,” along with a certain amount of capital and operational funding to ensure local governments could comply with the requirement.[10]

Focussing on Ontario but with reference to other provinces, this backgrounder outlines the specific role municipal governments play in Canada’s long-term care system, and how they collaborate with other orders of government to deliver, fund, and manage long-term care.

Municipal action within legal and fiscal constraints

Long-term care is not included in the Canada Health Act, and as a result is overseen exclusively by provincial and territorial governments, which have constitutional jurisdiction over health care and social services under Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Provinces and territories have responsibility for planning, funding, and managing government-owned long-term care homes; regulating, licensing, and (in most cases) subsidizing privately owned facilities; and setting and enforcing standards of care. Each has developed its own unique approach to these responsibilities, including greater or lesser roles for municipal governments.[11]

In Ontario, all incorporated municipalities have been required to deliver long-term care services since the 1949 Homes for the Aged Act, most recently revised in 2021 as the Fixing Long-Term Care Homes Act. The law requires that every single- and upper-tier municipality in Southern Ontario establish and maintain at least one municipal long-term care home; northern municipalities, which are more sparsely populated, are allowed to operate homes jointly with neighbouring municipalities.[12] As a result, 102 long-term care homes, almost one-fifth of the provincial total, are owned and operated by municipal governments, with a total capacity of 17,000 beds.[13]

The City of Toronto, for instance, directly owns and operates 10 long-term care homes with a total of 2,641 beds, serviced by more than 2,000 staff members (and another 2,000 volunteers) who together deliver culturally specific services and programming in several languages, at a cost of $360 million per year.[14] Similarly, Ontario’s second-largest municipality, the City of Ottawa, operates four long-term care homes with a total of 717 beds, at a cost of $97 million per year.[15] The same is true of many smaller, rural municipalities, such as the Municipality of Killarney (pop. 14,000), which broke ground on a new 14-bed long-term care facility in early 2023.[16]

Long-term care in Ontario is cost-shared by municipalities and the provincial government. In 2018, Ontario municipalities spent approximately $1.8 billion on long-term care (both operating and capital costs), with 46 percent of this total offset by provincial transfers.[17] In addition, many municipalities provide complementary services that benefit seniors and persons with disabilities, such as transit subsidies, grants to local community organizations, and drop-in centres. Overall, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario estimates that Ontario municipalities spend at least $2 billion per year to support seniors.[18]

In 2018, Ontario municipalities spent approximately $1.8 billion on long-term care (both operating and capital costs), with 46 percent of this total offset by provincial transfers.

Although Ontario is the only province that legislates municipalities to operate long-term care homes, some provinces permit municipalities to do the same. For example, Nova Scotia’s Homes for Special Care Act allows “municipal units” to create and operate long-term care centres, in accordance with provincial oversight.[19] A dozen of Nova Scotia’s 84 nursing homes are municipally owned, including in the Region of Queens Municipality, which has operated its own “home for special care” since the late 1800s.[20] Manitoba’s Elderly and Infirm Persons’ Housing Act enables municipalities (and other non-profit organizations) to own and operate personal care homes, historically referred to as “municipal homes for the aged,” either on their own or in partnership with neighbouring municipalities.[21]

For the most part, however, the municipal role in long-term care across Canada is limited. Where local authorities are involved, they usually consist of provincial health agencies operating at a local scale. For example, in British Columbia, long-term care falls under the jurisdiction of five regional health authorities overseen by provincially appointed boards, without any municipal input.[22] The same is true in other provinces that concentrate health care services into regional health units, such as New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as provinces that operate single provincial health authorities, such as Alberta and Saskatchewan.[23]

Municipal coordination with other orders of government

The federal government does not transfer money directly to municipalities that own, operate, or subsidize long-term care facilities. Still, the federal government plays an indirect role in delivering municipal long-term care services through bilateral agreements signed with the provinces. In 2017, the federal government reached separate agreements with provinces and territories to strengthen home care, community care, mental health, and long-term care for seniors, which was supplemented in 2021 by the Safe Long-Term Care Fund and common performance indicators to track outcomes.[24]

While it is difficult to determine exactly how much federal money reached municipal governments for long-term care, it is certainly the case, for example, that in April 2021, the City of Toronto reported funding a $17.1 million investment in long-term care centres, recognizing this as part of the combined federal and provincial monies made available during the COVID-19 pandemic.[25]

In response to the pandemic, the federal government also committed to developing an act to protect long-term care, which will propose national standards for long-term care, and encourage, but not require, provinces and territories to adopt the standards.[26] At the time of writing, however, there is no indication that federal or provincial officials involved in these discussions have meaningfully consulted municipal long-term care providers or other municipal stakeholders.

Despite the lack of meaningful participation in federal-provincial negotiations over the future of long-term care, many Canadian cities have adopted policies adjacent to long-term care. These policies encourage and support seniors and persons with disabilities to live healthy and comfortable lives – part of a growing, global, “age-friendly” movement.[27] For example, city councils in Vancouver, Calgary, and Montréal have adopted dedicated seniors’ strategies to adapt or tailor services that reduce loneliness and elder abuse, and ensure adequate housing and mobility options are available.[28] It is also common for municipalities to establish seniors’ advisory groups and committees, such as the City of Victoria’s Seniors Task Force, which informs its Seniors Action Plan.[29]

The idea is to help seniors “age in place,” by ensuring they have the health and social supports and services needed to live safely and independently in their own homes or communities for as long as they wish.[30] These policies create or foster “naturally occurring retirement communities” (NORCs), which are neighbourhoods that gradually come to house predominantly older populations.[31] According to researchers at Queen’s University, 37 percent of neighbourhoods in central Ontario function as NORCs.[32] In tandem with provincial and federal programs for seniors,[33] municipal age-friendly strategies aim to alleviate administrative burdens by offering subsidies, bylaw exemptions, and specific programming supports to these communities.

Conclusion

Long-term care is largely a provincial responsibility in Canada. Still, many municipalities, particularly in Ontario, operate their own long-term care facilities, which creates a minimum standard for the private sector to follow and enables municipal governments to observe the standards of care practised in the long-term care industry. Municipalities are also involved in care for seniors and people with disabilities through age-friendly strategies, which view urban design, city planning, bylaws, program and service delivery, and housing through a long-term care lens.

Municipalities: Central to the Future of Long-Term Care

By Pat Armstrong, PhD, FRSC

Pat Armstrong is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Sociology at York University.

Introduction: A short history

To situate the current role of municipalities in long-term care and to identify improvements in such care in the community, this paper begins with a short history of municipal involvement in this crucial care service. Specifically excluded from the Canada Health Act, long-term care varies considerably across Canadian jurisdictions. The focus here is on Ontario and its particular policies in relation to municipalities.

Ontario municipalities have long had a legislated role in long-term care, beginning with the Municipal Institutions Act in 1868 that required larger municipalities to establish “Houses of Refuge.” In the 1940s, the name and the focus were changed with the Homes for the Aged Act, and by 1949, all municipalities were required to have such a home. There was separate legislation for private, charitable, and municipal homes until 2007, when the provincial government brought them together under the Long-Term Care Act and applied the same regulations to all.[34] This legislation was repealed in 2021 and replaced by the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, which mainly focussed on incremental changes to staffing, reporting, and enforcement.[35]

Throughout these decades, the Province of Ontario provided regulations, inspections, and funding based on the number of people receiving care.[36] Today the funding to charitable, private, and municipal homes is based primarily on the assessed level of care required for each resident and is divided into four “envelopes”: Nursing and Personal Care, Program and Support Services, Nutrition Support, and Other Accommodation.[37] Additional provincial money is available for special areas or services and for capital development, but municipalities are required to build and contribute to at least one long-term care home.[38] After municipal amalgamation under the Harris government (1995–2002), more municipalities owned more than one home.

Resident fees are established by the Province; moreover, even the low fees are eligible for subsidies, so no one is excluded for financial reasons. A placement coordinator determines eligibility for admission, and eligible residents can list up to five homes they prefer. However, as the Ontario Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission reported, long waitlists usually mean applicants must take the first place available.[39] Current estimates indicate that nearly 40,000 people assessed as requiring 24-hour nursing and personal care in long-term care homes are on the waitlist.[40]And the 2022 More Beds, Better Care Act limits these choices further for people who are in hospital, waiting for long-term care.[41]

Better care, better work

There are many reasons why municipal homes are commonly the first choice of those seeking admission to long-term care.[42]

Perhaps most obviously, municipal homes tend to be closer to the applicants’ communities, and many of the decisions about them are made in the community. There is a local board responsible to the electorate, rather than a corporate board reporting to shareholders. Relatives and friends often live or work in the home, providing the promise of both social connections and some pressure from the community to provide good care. Community members are prepared to do volunteer work; family members are prepared to participate in family councils for peer support, education, advocacy, and organize activities that improve the experiences of all people in long-term care.

Less obvious is the higher rating of municipal homes on quality indicators like bed sores, falls, medication use, and hospital transfers.[43] These quality indicators in turn reflect staffing levels that are higher in municipal homes compared to for-profit and not-for-profit homes, while staff turnover is lower, contributing to continuity of care. The pay and benefits are also better in municipal homes, even though most staff in all three types of care homes have some union protections.[44] Although spending on nursing homes is often seen primarily as an expense to the municipality, it should be recognized that the pay and benefits contribute to the local economy.

Least obvious are the benefits of sharing strategies, information, and resources across and within municipalities. Our research on 10 Toronto care homes described how staff share experiences in areas such as different approaches to care and staffing or skill mixes, learning together how to make care and care work be as good as it can be given current resources.[45] There were also some significant savings in back office functions such as procurement and invoicing, gained by working together. During the pandemic, Toronto was able to move staff and managers around the homes to fill gaps and provide protections for families, residents, and staff, reducing outbreaks and deaths in their long-term care homes. When frontline workers had to declare a single employer, the City “was overwhelmingly the employer of choice.” Redeployed staff from non-essential City services assisted with screening, cleaning, feeding, and social engagement.[46]

There is undoubtedly room for improvement as multiple reports have made clear,[47] but the research clearly indicates that there are advantages to municipal homes for both residents and staff.

Improving care

Money, of course, matters, and more money is a necessary but not sufficient condition to improve care. The Ontario Long-Term Care COVID Commission described hearing “that in 2016, municipal governments collectively contributed $350 million over and above the provincial funding subsidy, not including capital expenditures (or approximately $21,600 per bed of additional funding).”[48] These funds help explain the higher quality care in municipal homes. But additional money is required to address growing and changing demands, requirements, and costs, and to improve the quality of care.

The Commission highlighted what research has been reporting for years, namely that more and more residents have complex care needs.[49] Today, one in three residents are highly or entirely dependent on staff, according to the Ontario Long-Term Care Association.[50] A majority have been diagnosed with a disease such as cancer or renal failure, and more than two out of five have a psychiatric or mood disorder.[51]

The change reflects a combination of factors. The number of beds was reduced in psychiatric, chronic care, rehabilitation, and acute care hospitals; in the 1990s, Ontario closed 31 public, six private, and six provincial psychiatric hospitals sites.[52] At the same time, more and more people survived well past age 65, with complex health issues that required advanced care skills. Today the care home population is more diverse culturally, racially, linguistically, and in terms of gender; there are both more people under 65 and more men in long-term care. Meanwhile, most private households are not equipped, in terms of the physical space or the skills, to deal appropriately with such needs.

As a result, care homes require more staff, and more highly trained staff, as well as more specialized equipment. The Ontario government has recognized this in part by setting a target of four hours of direct care per resident per day and some additional time for allied health professionals.[53] It has also made permanent the $3-an-hour wage increase for personal support workers that was introduced during the pandemic. However, it should be noted that the four-hour minimum comes from a 2001 study in the United States and more recent research indicates that the rising complexity of care needs means significantly higher minimums are required.[54] The hourly wage increase will not be sufficient to retain, train, and increase staff numbers and maintain good quality care at current levels, let alone meet growing demands. Moreover, there is pent-up demand for wage increases, given the one percent wage cap on public-sector wages imposed in 2019 for three years by Bill 124.[55]

As the Commission points out, however, only some of the municipal funding goes to wages; other essential care is also supported by municipal money. Food is just one example. Although the Province has provided some additional money for food, the limited amount (slightly less than $10 a day per resident) makes it very difficult to absorb rising prices and meet the new standards for flexible, good quality meals. Similarly, there is some additional provincial funding for personal protective equipment, but not enough to cover the full costs of meeting the new standards.

Municipal homes also need more funding for infrastructure. Although most of the homes with four-bed rooms are in for-profit facilities, some municipal homes still have them, even though they were supposed to be phased out long ago. And now, in the wake of COVID-19, the Canadian Standards Association’s new guidelines recommend all single rooms and smaller household units.[56] A number of the municipal homes are older and require major renovations or entire rebuilds, especially if they are to meet new infection standards. Some one-time funding is available to municipalities to do major renovations or build new facilities, but not nearly enough to cover the costs.

Good quality care takes time and resources, only some of which cost money. Demands for change and models for transformation have been around since the 1960s, but COVID-19 has brought new urgency. These models are predicated on understanding care as a relationship and attending to individual preferences. They in turn require continuity of care providers, along with autonomy and flexibility for staff to be able to focus more on social care, rather than on tasks and clinical care, supported by leadership committed to these principles.[57] The 2023 standards of the Canadian Health Service Organization (HSO) are very much in keeping with these principles. In addition, they recognize that the conditions of work are the conditions of care[58] and that team-based care should promote equity, diversity, inclusion, and cultural safety.[59]

Conclusion: Moving ahead

The research makes it clear that, comparatively speaking, municipal homes provide the best care and working conditions, while for-profit homes provide the lowest quality of both care and working conditions. It therefore makes sense to invest in municipal homes and not invest in those that are for-profit. Municipalities have the fewest revenue sources of all levels of government, and they already offer as much funding as they can. As the HSO standards make clear, “adequate and coordinated federal and provincial/territorial investments and funding into services provided in LTC [long-term care] homes” is a starting point. By tying the funding to the building of homes linked to communities, prohibiting profit, and implementing the new HSO standards, the federal government could support the expansion and improvement of municipal long-term care homes.

Municipal homes provide the best care and working conditions, while for-profit homes provide the lowest quality of both care and working conditions.

The HSO standards address a wide range of issues, including governance, staffing, working conditions, and approaches to care in ways that could significantly improve the quality of care and care work, some of it with little or no additional cost. The Ontario government has allocated some additional funding for new beds (a significant proportion of which is provided to for-profit companies), increased staffing levels, staff training, and wages, but has offered no specific money for strapped municipalities or given them priority, despite their stressed finances and higher quality care and work.

Some of this investment, financial and otherwise, should be used to support coordination and sharing of services, knowledge, and experiences among municipal homes to build on their expertise and implement the new standards of care in ways that respond to the needs of their particular communities. At the same time, establishing the means to connect municipal and non-profit homes could further promote learning about promising practices, from and with each other. Municipal homes have long played a critical role in long-term care, not only in providing a necessary service but also in leading the way in good quality, responsive care. They deserve and need financial and other supports if they are to continue to do so.

Planning for Age-Friendly Communities

By Daniella Balasal, MCIP, RPP, PMP and Nadia De Santi, MCIP, RPP

Daniella Balasal is a Registered Professional Planner and an accredited project management professional who is committed to the development of inclusive and livable communities.

Nadia De Santi, MCIP, RPP is a Practice Lead with WSP Canada Inc. with more than 20 years of experience in policy planning, land development, and community and Indigenous engagement.

Introduction: What is an age-friendly community?

The World Health Organization (WHO) first described an age-friendly city in 2007 as one that encourages active aging by optimizing opportunities for health, participation, and security to enhance quality of life as people age.[60] This description applies to any community, regardless of whether it is primarily an urban or rural municipality, or a mixture of the two. The WHO further identified eight dimensions, or aspects, of community life that overlap and interact to directly affect older adults.

In 2023, the WHO further defined these dimensions as “domains of action” in its National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide,[61] illustrated in Figure 1. It provides a foundation for planning, including checklists that a community can use to assess how age-friendly it is against each domain of action.

Figure 1. Age-friendly city or community “domains of action”

Source: World Health Organization, National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide, 2023.

Age-friendly communities are more than hard infrastructure

Of the WHO’s eight community domains of action, only three can be referred to as “hard” infrastructure: outdoor spaces and buildings; transportation; and housing. The remaining five are the social or “soft” infrastructure components of an age-friendly community: social participation; respect and social inclusion; civic participation and employment; communication and information; and community support and health services. What does this imply?

The concept of age-friendly community planning requires a holistic approach, and needs to be applied, or at least considered, in any public or private initiative. For example, while a community may offer numerous opportunities for civic participation and employment, if essential information is not provided through a variety of communication methods (for example, in different languages), then the ability of a member of the public to actively participate and find employment is limited. As a result, the community could not be said to be as age-friendly as it could be.

How did age-friendly community planning start?

Age-friendly community planning can be traced back to 1982, the year that the United Nations first gathered national governments for a World Assembly on aging populations. In 1986, the WHO organized the First International Conference on Health Promotion, where the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion was signed.[62] This Charter was a call to action to achieve “Health for All” by the year 2000 and beyond.

Almost 20 years later, the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (MIPAA) was adopted at the second United Nations World Assembly on Aging. The MIPAA focussed on the need for international and national action on three priorities:

- Older people and development.

- Health and well-being through the life course.

- Ensuring environments enable and support health and well-being.[63]

In 2007, the WHO established that age-friendly community planning benefits people of all ages and abilities in its Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide.[64] Understanding of age-friendly communities has come a long way since the WHO established the link between health and well-being.

Exploring the role of municipalities in meeting the needs of aging communities in Ontario

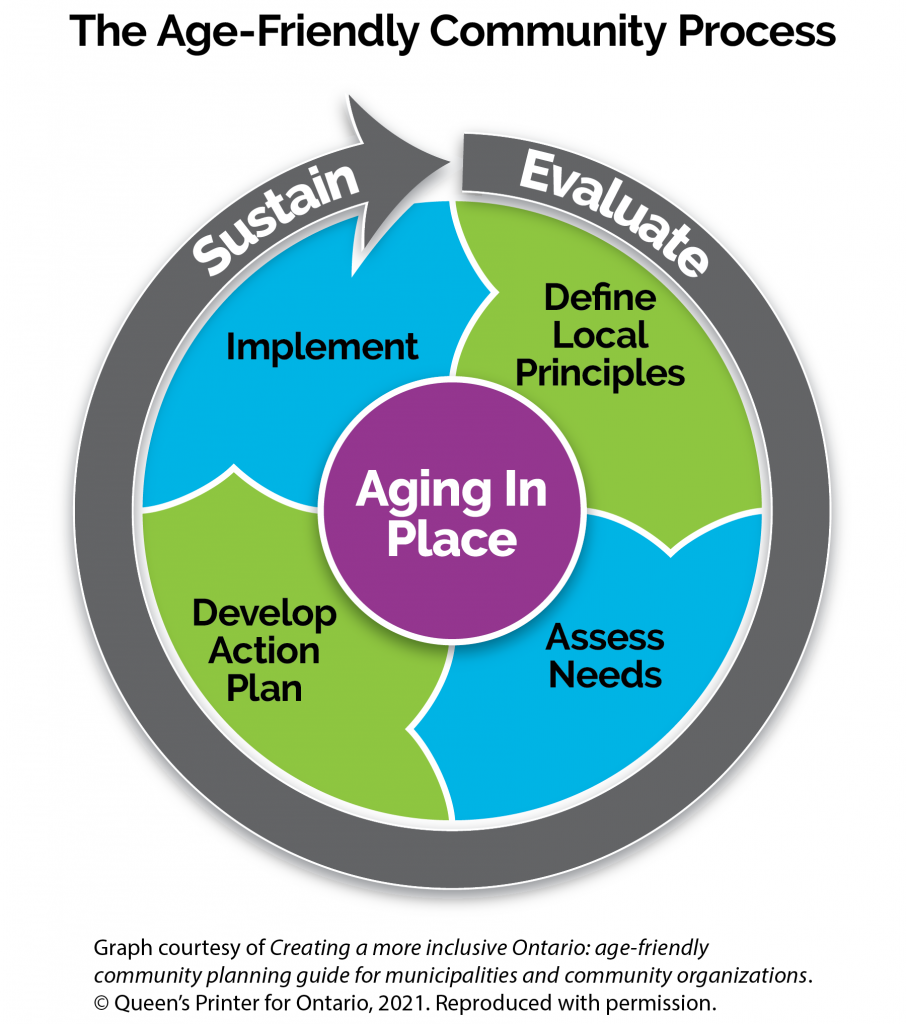

In 2021, the Province of Ontario updated its guide to age-friendly communities, Creating a More Inclusive Ontario: Age-Friendly Community Planning Guide for Municipalities and Community Organizations.[65] It provided success stories and numerous practical references for municipalities to use in preparing an age-friendly community action plan. The guide also provided a four-step process, as illustrated in Figure 2:

1: Define local principles.

2: Assess need.

3: Develop action plan.

4: Implement and evaluate.

The guide also emphasized discussing governance as part of the visioning work in Step 1, as well as the need for accountability by the organization preparing and implementing the age-friendly community action plan.

Figure 2. The Age-Friendly Community Action Plan development process

Source: Government of Ontario, Creating a More Inclusive Ontario: Age-Friendly Community Planning Guide for Municipalities and Community Organizations, 2021.[66]

Many municipalities across Ontario have committed to developing local age-friendly community action plans, as well as community assessments (discussed below). To explore the current state of municipal initiatives, including the ways in which community needs are being addressed, we reviewed the status of municipal age-friendly and senior-focussed plans and strategies.

Review of municipal plans and strategies

We conducted interviews with local government staff members in communities that had local age-friendly community action plans at various stages of implementation, from early rollout to a subsequent cycle of strategy and reiteration. We sought to confirm the status of work on age-friendly plans, their alignment with the WHO domains of action, and how action items are being implemented. Interviews also included an in-depth review of allocated resources and funding commitments. Interviewees were known to be actively involved in leading age-friendly initiatives or recognized as subject matter experts in the City of Toronto, the City of Brampton, the Town of Caledon, and the County of Grey.

Balancing competing age-friendly priority areas to address local needs

Our study found that municipal age-friendly strategies and plans in Ontario have generally been developed to broadly align with the WHO’s eight domains of action. There were modest variations in language to reflect the unique needs of different communities and areas of jurisdiction, such as whether a municipality served a regional function or was a single-tier local government.

Implementing these strategies and plans has focussed on both hard and soft infrastructure: the built environment, including housing, transportation, and the design of public spaces, as well as civic engagement and participation, social inclusion, communication, and health.

For example, the City of Brampton developed a digital seniors’ resource guide that provides free information to help residents identify available local organizations and community supports. Its online platform features content that aligns with the eight domains of an age-friendly community, providing quick access to information and resources to meet the needs of older adults and caregivers alike.

Brampton also worked in partnership with its Downtown Business Improvement Association and the non-profit 8 80 Cities to host a pop-up outdoor holiday market as an age-friendly initiative. The 2022 Active Downtown Brampton event was geared to seniors, bringing a laneway to life through interventions that enhanced pedestrian friendliness. The focus was on encouraging leisure and enjoyment of public space, stimulating visual senses for a heightened experience for those visiting the city’s downtown area. Yoga, a photo booth, and vendors were incorporated to attract and accommodate attendees over 50.

Further approaches can be found in the Town of Caledon and the County of Grey, where developers are being directed to build senior-friendly housing options, following advocacy by committed community and municipal staff members. For example, the housing options include accessory units that accommodate live-in caregivers. In addition, the Town of Hanover has created an age-friendly guide on how downtown businesses can improve access to services to meet the needs of the aging population, while the City of Toronto’s Seniors Services and Long-Term Care team partnered with council members to host interactive webinars that raised awareness of the wide range of programs, incentives, and services available to seniors and caregivers.

Political champions are essential to maintaining the commitment

The staff representatives we interviewed emphasized the importance of political support. A municipal council member that champions age-friendly objectives is essential to the success of any age-friendly community action plan. Generally, age-friendly strategies and plans were unanimously approved or endorsed by council members, along with commitments to establishing goals and action items.

Municipal staff members noted that it is critical to build long term buy-in that extends beyond the typical four-year council term. In many communities, newly elected council members lacked familiarity with past age-friendly initiatives and priorities. Staff members often needed to make a dedicated effort to build up knowledge and renew the commitment to continue with age-friendly initiatives. They did this through onboarding sessions, briefing an incoming council member on age-friendly activities.

In some communities, elections resulted in a shift in a council’s areas of focus. For an age-friendly community action plan, this could result in a loss of funding as projects and areas of investment are reprioritized to reflect the new council’s emerging areas of interest. Additional time is often needed to re-establish priorities, regain ground and momentum, and rebuild consensus around age-friendly plans and strategies. In one community, the need to maintain an existing age-friendly task force or committee is now coming into question.

An age-friendly lens on local processes, policies, and decision making

Municipal policymakers have land use planning instruments, such as local official plans, zoning bylaws, and urban design guidelines, through which they can advance age-friendly initiatives. Land use policies, for example, can promote aging in place principles in matters relating to the design of public spaces, transportation corridors, the housing continuum, and infrastructure.

Municipalities that have incorporated age-friendliness into local land use plans include the County of Grey and the City of Brampton. The County of Grey has created the Healthy Development Checklist: A Tool to Help Guide Healthy Community Development.[67] This guide is used by both staff members and developers to assist with the evaluation of development proposals that support active aging. Similarly, the County of Grey’s Healthy Community and Subdivision Guidelines include age- and family-friendly design considerations, such as wheelchair ramps, accessible washrooms, and benches at appropriate heights to increase access to public services used by seniors.[68] Both documents are currently being used as key resources to support municipal decisions.

In Brampton, planning staff members are seeking to incorporate policy terms and definitions that promote age-friendly objectives into the official plan review process to ensure that future developments meet the needs of the aging population. From the outset of the design planning stage, developers would be required to consider built form, housing, and transportation. Other specific requirements could include designing streetscapes to be pedestrian-friendly for all residents, such as seniors using mobility devices or families using strollers.

Another policy area being explored at the local level is how well municipal age-friendly implementation efforts align with the rollout of climate change policies and climate resiliency plans. Many communities across Ontario have recently developed climate action plans to advance their sustainability goals. These plans are often consistent with the requirements of a healthy built form that allows residents to age in place.

Two innovative approaches that bring together age-friendly objectives and climate resiliency, and even extend their impacts, include a mapping project that identifies the locations of community gardens throughout Grey County, and an initiative that seeks to strengthen the connection of bike trails between Grey County and neighbouring Bruce County. These projects demonstrate that, “Cities and communities are the places where policy meets people, where the impacts of the decisions of what we do or not with our environments are most keenly felt.”[69]

A commitment to transparency and accountability

A steadfast commitment to transparency and accountability is paramount for the ongoing success of local age-friendly initiatives. It starts with a clear vision. For example, the City of Toronto’s Seniors Strategy Version 2.0: Final Report seeks to “reshape Toronto into a place where diverse seniors can age with comfort, dignity, and access to the supports they need to thrive.”[70]

Leveraging the expertise of the Toronto Seniors Strategy Accountability Table, a multi-sectoral stakeholder group, has proven successful in implementing the strategy.[71] To date, all the recommendations from Version 1.0 have been implemented, as have 24 of 27 from Version 2.0, with the remaining three well underway. The Table was integral to making progress,[72] and its members continue to remain engaged with the City through quarterly meetings and monthly email updates that distribute information on programs, policies, events, and resources for seniors.

Similarly, the Town of Caledon’s Seniors Task Force serves to steer its Age-Friendly Caledon Action Plan 2021–2031. The Task Force includes community members who serve as advocates to ensure that “residents are able to age well and age in place in the community,”[73] guided by a terms of reference.[74]

In general, communities have benefitted from having an established oversight body and community assessments. Regular reporting and updates to the local council also help to ensure there is transparency and accountability. For example, in 2021, the City of Brampton prepared an assessment after its council endorsed the 2019 Age-Friendly Strategy and Action Plan, to report on implementation achievements.[75] Currently, City staff members are preparing a subsequent report on recent accomplishments, next steps, and how City departments and the broader community are implementing its recommendations.

How municipalities can stay the course

To effectively implement age-friendly community action plans and strategies, dedicated funding and resources are required.

To ensure long-term commitment, funding for age-friendly projects must be incorporated into municipal budgets, with direct alignment to the age-friendly priorities that are established in local plans. Dedicated staff resources must also be part of the planning, considering the reality of staff workloads, for example, along with ensuring project leads have the resources required to achieve program and plan goals.

To implement age-friendly plans, municipalities also need to ensure community members remain engaged. For example, by providing opportunities to join age-friendly task forces or committees, the community can hold council members and the municipality accountable for promises and ensure that work continues.

In addition, an ability to be nimble is an essential quality for municipal governments to be able to respond to the aging demographic and ever-shifting global realities. In the City of Brampton, for example, during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, supports for local seniors were temporarily modified to accommodate shifting needs. The City mobilized staff members to prioritize essential services, including creating a new one-year program dedicated to delivering groceries and medications.

Recommendations

Municipalities that are considering an age-friendly community action plan should first undertake an age-friendly community assessment, particularly where there is limited funding or resources. As a low-cost win, undertaking a community assessment or audit based on the WHO’s age-friendly checklist helps to gauge how the community measures against the criteria.

Municipalities should apply an age-friendly lens to local programming, such as the recreational services they offer or how local parks and public spaces are being used. In addition, design details that accommodate the physical needs of all age groups and abilities should be part of the planning of new parks and recreation facilities, or the revamping of older parks and facilities, as communities grow.

Municipally owned buildings and sites, and school properties, also offer opportunities for multi-generational events and activities, such as community gardens, where sustainability priorities and projects can be multi-purposed to meet the shifting needs of residents and the aging population.

In addition, municipal climate change policies and climate resiliency plans provide a further opportunity to promote aging in place objectives. Plans that promote sustainability should incorporate concepts of livability that integrate accessibility and inclusion for all ages.

Provincial and federal governments can also support age-friendly priorities through grants and other funding programs, such as a long-term commitment to the federal New Horizons for Seniors grant. This could include submission criteria that aligns with global age-friendly dimensions, and increases funding allotments and grant programs to support local initiatives.

Conclusion

Age-friendly community planning has been around for 40 years and is here to stay. It changes the way everyone experiences the community. Any municipality or community that carries out an age-friendly community action plan, or at minimum a community assessment, will learn how well that locality is meeting the needs of the aging population. Most people will experience some mental or physical challenges within their lifetime, so we ask, why not create the best public spaces, opportunities for all, and a better path for future generations?

Age-friendly planning encompasses all aspects of life. As a concept, it inherently embodies principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion through at least three of the WHO’s domains of action that support an age-friendly community: respect and social inclusion, civic participation, and social participation (see Figure 1). Municipalities can support the achievement of these domains of action as an important partner in aligning the delivery of services and community design by actively applying an age-friendly lens to community planning processes, policies, and decision making.

An Intergovernmental Vision for Long-Term Care

By Shirley Hoy

Shirley Hoy is a Senior Advisor with StrategyCorp.

The views presented in this paper are her own.

Introduction

The 85 recommendations in the Ontario Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission’s Final Report, released in April 2021, addressed many different aspects of seniors’ care. Given my previous work in the Community Services Department of the former Metro Toronto, and later in the amalgamated City of Toronto, I was most interested in the analysis and recommendations for the three types of long-term care providers: for-profit, non-profit, and municipal.

Out of 626 long-term care homes in Ontario, caring for more than 78,000 residents, 58 percent are for-profit, 24 percent are non-profit, and 16 percent are municipally owned.[76] Among the 85 long-term care homes in Toronto, the largest city in the country, the municipality also owns the smallest share: 46 percent are for-profit, 43 percent are non-profit, and 11 percent are municipally owned.[77]

As the share of homes directly operated by municipalities in the province, and by the City of Toronto, is less than 20 percent of the whole system, it seems reasonable to question whether municipalities should continue with their current role, and what the implications would be if they were to relinquish this role to the for-profit and non-profit sectors.

In this paper, I consider this policy matter by addressing the following questions:

- First, why now? Is this policy examination urgent?

- How should long-term care restructuring work, in the broader context of elder care reform?

- How has the municipal role in both long-term care and elder care evolved over time?

- Finally, is there a more distinct role for municipalities in elder care reform?

This paper starts with a description of the key elements of a reformed elder care system, followed by a brief review of the current role of municipalities in providing seniors’ services, and concludes with three specific recommendations for an enhanced, unique leadership role for municipalities in elder care, by

- fostering care innovation in the long-term care sphere;

- actively partnering in the proliferation of naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) with supports; and

- sustaining a “public eye” on the entire elder care system to ensure robust transparency and accountability.

The urgency of policy examination

There is a worry, and an opportunity, which provide the impetus for policy consideration at this time. The worry is the demographic shift at our doorstep. The 2021 Census revealed that more than 30 percent of Canadians are over 55[78] and this share is slated to grow.[79] Moreover, there were more than one million more seniors over 65 than there were children under 15,[80] almost 10 times more than in 2016, when there were 96,000 more seniors than children. To quote journalist John Ibbitson, “We are no longer an aging society. Our society is now aged. And we’re not ready.”[81] In Ontario in particular, the population over 75 will grow to more than 2.6 million by 2040, from 980,000 in 2015.[82]

Given this grim reality, simply constructing more long-term care beds will be woefully inadequate. Additionally, focussing on this strategy alone will take us further away from the much-touted goal of enabling seniors to live and thrive in their own homes.

What, then, is the opportunity? It is rooted in the February 2023 health care funding agreement announced by Ottawa with the provinces and territories. It involves a 10-year plan to spend $196.1 billion, with $46.2 billion in new funds to be negotiated in bilateral agreements. Priority areas include primary care reform, human resource planning and enhancement, mental health, health system modernization and digitization, and elder care (both home care and long-term care).[83]

Having elder care clearly identified as one of the priorities of health care reform provides much greater scope for restructuring long-term care as an integral part of community support and care to which seniors should have access. As Dr. Katherine Smart, the president of the Canadian Medical Association asks, “Why is home care and long-term care not an integrated part of one health care system?”[84]

The notion of a “campus of care” model that integrates long-term care homes into the broader health care system is also being championed by leaders in health care and social services. At the University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto, President and CEO Dr. Kevin Smith is aiming to make navigating the hospital, long-term care, and the community as seamless as possible. UHN itself operates a rehab institute, a hospice, programs for people without housing, and a long-term care home, in addition to its acute care hospitals.[85]

Restructuring in the context of elder care reform

There was extensive media coverage of the horrific deaths in long-term care facilities in the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, 61 percent of COVID deaths in Ontario occurred among long-term care residents. By the end of April 2021, 11 staff members and almost 4,000 residents had died.[86]

In response, the provincial government announced it would redevelop and construct 60,353 beds by 2028, with 31,705 new beds and 28,648 upgraded beds.[87] But the need for beds is enormous, with almost 40,000 Ontarians waiting as of October 2022.[88]

Therefore, I agree with those who say building more of the same will be an utter waste of money. There is an urgent need to reposition long-term care homes in a completely transformed context of elder care, consisting of tiers of care and support, at the centre of which are individual seniors, trying to live and thrive as their health and social circumstances change.

From the lessons learned through the tragic losses in several long-term care homes, there has been a great deal of public discourse on their fundamental restructuring, in a completely different way, which is “person centred,” or “emotion centred.” But what does that really mean?

This is a method of care often called “the Butterfly Approach,” first developed in the U.K. by Meaningful Care Matters.[89] Rather than focussing solely on the medical needs of a senior, a full assessment of their background is undertaken. With that understanding, care and support are provided in a homelike environment, with a consistent staff team. This stable approach to care is beneficial to both staff members and the seniors.

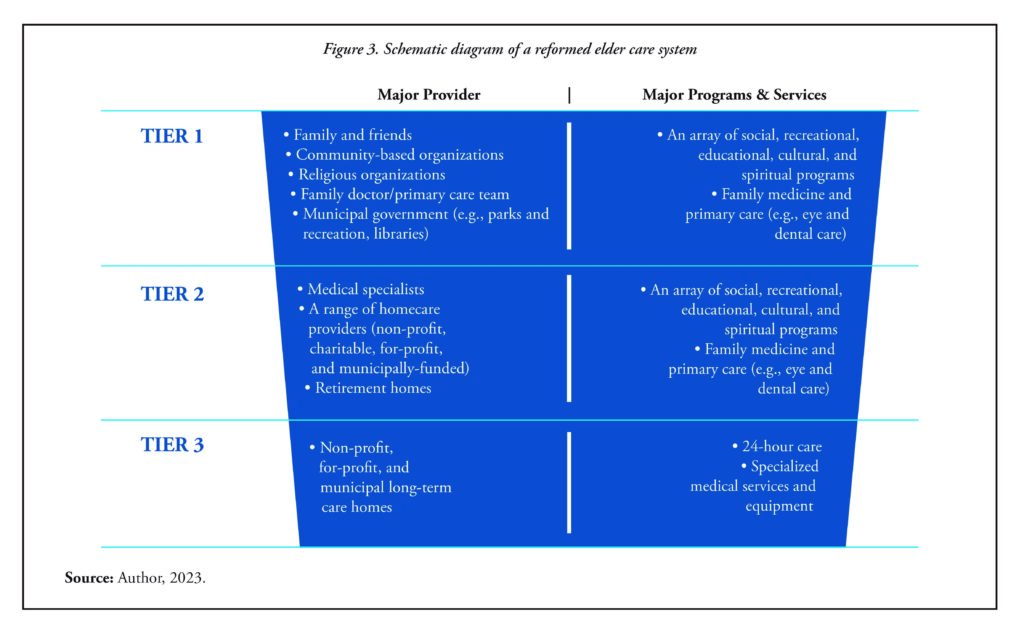

I envision the reformed elder care system as follows (see Figure 3):

Tier 1: At the top tier, the broadest level, is the individual. If in reasonably good health, this person would be an engaged member of the community, receiving support and care from family members and friends, and an array of social, recreational, educational, cultural, spiritual, and community health networks, including access to a family doctor and other primary care providers, such as a dentist and an eye doctor. Municipal departments (for example, parks and recreation, library services, public health) would be major providers of programs and support.

Tier 2: As the person ages, the second tier involves fewer general community activities, and more interaction with the family doctor, medical specialists, and acute care institutions for possible operations, rehabilitation, and recovery. This would require health supplies and equipment, and home care nurses and personal support workers. While more health professionals would be called on to offer care in this tier, a variety of home care supports, delivered by several different non-profit and for-profit organizations, would be the main service providers. Often these entities would be funded by the municipal government.

An encouraging development in long-term care is the concept of NORCs, which are found in several different municipalities in Ontario, including Hamilton, London, Kingston, and Toronto. A NORC is “a building, neighbourhood or region that without intention is home to a significant number of older adults.”[90] By extension, a “NORC with supports” is a system of elder care in which health, social, or educational supports are brought into the homes of seniors, where they already live.[91] Recent research has suggested that Ontario has nearly 2,000 residential buildings that could be considered NORCs, home to populations where at least 30 percent of residents are older than 65.[92]

At present, there is no dedicated government funding for NORCs with support programs in Ontario. Leadership has been mainly provided by family caregivers, community organizations, municipal services, and hospital and university researchers (from McMaster University, Queen’s University, University Hospital Network–Toronto Metropolitan University, and Western University). There is an opportunity here for municipalities to be much more active partners in the further development of NORCs with support programs.

Tier 3: In the third tier of a reformed elder care system are seniors who have increasingly complex medical, physical, and cognitive needs, and are unable to manage daily living activities. Specialized medical equipment and 24-hour care are required, along with placement in a long-term care home.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of a reformed elder care system

Figure 3 (text): Schematic diagram of a reformed elder care system

| Tier | Major Provider | Major Programs and Services |

|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | Family and Friends | An array of social, recreational, educational, cultural, and spiritual programs |

| Community-based organizations | Family medicine and primary care (e.g., eye and dental care) | |

| Religions organizations | ||

| Family doctor/primary care team | ||

| Municipal government (e.g., parks and recreation, libraries) | ||

| Tier 2 | Medical specialists | An array of social, recreational, educational, cultural, and spiritual programs |

| A range of homecare providers (non-profit, charitable, for-profit, and municipally funded) | Family medicine and primary care (e.g., eye and dental care) | |

| Retirement homes | ||

| Tier 3 | Non-profit, for-profit, and municipal long-term care homes | 24-hour care |

| Specialized medical services and equipment |

Source: Author, 2023.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, public debate had focussed on the inadequacy of government funding for home care, as well as on the quality and quantity of care in the long-term care sector. The past three years of the global virus brought home the enormity of this festering crisis; that is, the total inadequacy of Tier 2 and Tier 3 levels of support and care for seniors.

In spite of a spate of announcements by the Ontario government – dealing with the inadequacy of wages for personal support workers and nurses; injecting new dollars in the home care sector; improving staffing and adding care hours for long-term care residents; upgrading long-term care homes; and adding new long-term care beds – the critics and the general public continue to say, “Not enough, and not fast enough!”

What, then, is missing? I contend that in the current elder care sphere, the most fundamental failing is the lack of clear, visible leadership for determining and reporting on the impact of investments on the front line, at the community level.

I propose that in Ontario, given the historical role of municipalities as service managers for social services and “homes for the aged” (now “long-term care homes”), they can assume a critical new role in ensuring provincial funding is employed with greater impact in Tier 2 and Tier 3 of a reformed elder care system.

The current role of municipalities in seniors’ services

AdvantAge Ontario’s November 2022 report, Ontario Municipalities: Proud Partners in LTC, provides an excellent chronology of the social service roots of municipalities in providing care to seniors, dating back to 1868.

With the adoption of the Homes for the Aged Act in 1947, modest standards and partial funding were established for Homes, and then the 1949 updated legislation mandated all municipalities to establish a Home for the Aged. Decades later, in 2007, the government made a significant change to the name of the legislation, to the Long-Term Care Homes Act, and then most recently in 2021, to the Fixing Long-Term Care Act. Every successive legislative update still required municipalities to continue their role in long-term care (LTC).

Whether by design or good fortune, recognition of the social service roots of municipalities enables a “public eye” on the whole elder care system, so that healthy and sustainable communities are developed.

“The current mandate for the municipal delivery of LTC services as set out in the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, specifies that every upper- or single-tier southern municipality is required to maintain at least one municipal home, individually or jointly, while northern municipalities may operate one individually or jointly.” (AdvantAge Ontario November 2022).[93]

As some municipal elected leaders and senior administrative staff have asked, given the growing array of property-related services and funding responsibilities, why not leave it to the for-profit, non-profit, and charitable entities to offer elder care?

In my view, whether by design or good fortune, recognition of the social service roots of municipalities enables a “public eye” on the whole elder care system, so that healthy and sustainable communities are developed. The City of Toronto offers an illustrative case study.

Municipal innovation in long-term care

Following the creation of Metro Toronto in 1953, the regional government built 10 homes for the aged over the span of five decades. The homes were located in the diverse six local constituent municipalities of East York, Etobicoke, North York, Scarborough, Toronto, and York. The first one, Kipling Acres, was built in 1959, and the most recent, Wesburn Manor, was built in 2003 (after the dissolution of Metro and the amalgamation of the six municipalities). In total, Toronto has 2,600 long-term care beds.[94]

As in other municipalities, City of Toronto Council approved additional capital and operating funding over the years. This was directed to enhancing staffing levels and social and recreational programs, above provincial funding subsidies and program requirements, and to upgrading outdated building standards.

My experience suggests that, because of strong networks in the community and in key divisions of the municipal public service, such as public health, welfare, and social housing, Metro Toronto’s homes for the aged promoted innovation in long-term care and the broader elder care system in the community. In discharging its concomitant responsibility for managing the social service system, Metro Toronto funded community organizations serving seniors living in the community, from shelters to social recreational program to Meals on Wheels. These programs were often delivered in partnership with others, such as the United Way.

From this history and tradition, the former Metro Toronto Homes for the Aged Department is now called the Seniors Services and Long-Term Care Division in the amalgamated City of Toronto. I think the new title for the division is important, signalling its primary role in providing seniors’ services. It describes its mandate as the “planning and strategic integration of City services for seniors, including community support programs, such as adult day programs, supportive housing services, tenancy supports, and homemakers and nursing services for vulnerable individuals who reside in the community.”[95] That is, its mandate centres on programs and services beyond the walls of its 10 long-term care homes, in the broader community, to enable seniors to live with support and age with dignity.

A unique role for municipalities

As the City of Toronto case study demonstrates, in adhering to their minor share in the long-term care segment of the elder care system (as defined by provincial legislation, the Fixing Long-Term Care Act), municipalities can and should assume a leadership role for elder care reform, to address the following three key objectives:

- Within long-term care homes, foster innovation by introducing and testing new models of care (for example, the Butterfly Approach, as in the Region of Peel, and emotion centred care, as in the City of Toronto). The key features of these models include smaller, homelike units, infection prevention upgrades, and consistent medical and social staff teams to ensure the holistic well-being of residents. Service delivery always has an eye on both the quality and quantity of care needed, and providing care with other community partners, where possible.

- Enhance and expand the municipal system management role in elder care reform. This would involve collaborating with key community and academic partners to increase Tier 2 support and care for seniors, especially through NORCs with supports, in municipalities across the province.

- Implement well, with clear objectives and delivery milestones. This would include reporting regularly and publicly on both achievements and shortcomings in implementation, and, in collaboration with key academic, health, and community experts and leaders, undertaking robust impact evaluations at the community level, starting with low-income communities, where the needs are the greatest.

Conclusion

One of the silver linings from the devastation of the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic is that across the country, there is now wide and deep recognition that elder care reform is urgent, not just in long-term care homes. As health journalist André Picard notes, “While more money is no doubt necessary to meet the needs of the growing population of elders, a recalibration and commitment to keeping people in the community is just as important.”[96]

It is time to act: to innovate, integrate, and collaborate. It is time for a different approach, different governance structure, and different leadership to be founded. In this regard, the critical role of municipalities in developing and sustaining healthy communities means that they should be responsible for ensuring integrated elder care reform takes hold.

About the Contributors

Pat Armstrong is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus at York University and a Fellow of the Royal Society. A feminist political economist who studies social policy, women and work, health, and social services, she has led multiple research projects in partnership with a range of organizations. Among her many publications, she is editor of Unpaid Work in Nursing Homes: Flexible Boundaries; Care Homes in a Turbulent Era (with Susan Braedley); Wash, Wear and Care: Clothing and Laundry in Long-Term Residential Care (with Suzanne Day); and The Privatization of Care: The Case of Nursing Homes (with Hugh Armstrong). Among her many publications, she is also co-author of “Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care,” a report prepared for the Royal Society of Canada. She also served as a member of the Health Standards Organization’s technical committee, which developed standards for long-term care, and on the independent Science Table’s congregate care working group (Ontario).

Daniella Balasal is a Registered Professional Planner and an accredited project management professional who has worked in the municipal sector for more than 12 years. She is committed to the development of inclusive and livable communities. Her experience spans affordable housing, social policy, innovation, land use planning, community development, and age-friendly community planning.

Nadia De Santi is a Practice Lead with WSP Canada Inc. and has more than 20 years of professional planning experience, including municipal policy and land development approvals. Her diverse experience ranges from federal campus master planning to provincial highest and best use analyses to municipal planning and policy projects. Her local experience includes preparing official plans and zoning bylaws; developing community improvement plans and age-friendly community action plans; and providing planning services. She also prepares land use plans and zoning bylaws for Indigenous communities. She is adept at building client relationships, managing multi-disciplinary project teams, and working with approval agencies. She is passionate about community engagement and facilitation, and makes it a priority to understand and address local community issues and values. She has obtained a Certificate of Completion in “Working Effectively with Aboriginal Peoples™ for Governments” and in the International Association of Public Participation’s “Foundations in Public Participation” (Planning and Techniques modules).

Shirley Hoy is a Senior Advisor at StrategyCorp and a Board Member of IMFG. She has had a distinguished public service career, including serving as City Manager with the City of Toronto and as Assistant Deputy Minister with three Ontario ministries. Over the course of her career, she has held various policy and planning-related positions, including in the former Metro Toronto government, where she started in the Department of Community Services and went on to serve as General Manager of Administration/Corporate Secretary of Exhibition Place; as Executive Director of the Metro Chairman’s Office; and as Commissioner of Community and Neighbourhood Services, where she provided leadership on major services including social assistance, homes for the aged, housing and support, public health, and parks and recreation. Following her term as Toronto City Manager, she served for five years as CEO of the Toronto Lands Corporation.

Acknowledgements

Pat Armstrong’s paper draws on the following federally funded research, for which she is Principal Investigator:

- “Learning from the pandemic? Planning for a long-term care labour force,” SSHRC Insight Grant, 2022–2024.

- “COVID-19, families, and long-term residential care,” SSHRC Partnership Engage Grant, 2021.

- “Changing places: Paid and unpaid work in public places,” SSHRC Insight Grant, 2017–2021 (extended through 2023).

Shirley Hoy expresses her thanks to Enid Slack and Kass Forman for their advice and support in the development of her paper.

About the Who Does What Series

Canadian municipalities play increasingly important roles in addressing policy challenges such as tackling climate change, increasing housing affordability, reforming policing, and confronting public health crises. The growing prominence of municipalities, however, has led to tensions over overlapping responsibilities with provincial and federal governments. Such “entanglement” between orders of government can result in poor coordination and opaque accountability. At the same time, combining the strengths and capabilities of different orders of government – whether in setting policy, convening, funding, or delivering services – can lead to more effective action.

The Who Does What series gathers academics and practitioners to examine the role municipalities should play in key policy areas, the reforms needed to ensure municipalities can deliver on their responsibilities, and the collaboration required among governments to meet the country’s challenges. It is produced by the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance and the Urban Policy Lab.

About IMFG

The Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance (IMFG) is an academic research hub and non-partisan think tank based in the School of Cities at the University of Toronto.

IMFG focusses on the fiscal health and governance challenges facing large cities and city-regions. Its objective is to spark and inform public debate, and to engage the academic and policy communities around important issues of municipal finance and governance. The Institute conducts original research on issues facing cities in Canada and around the world; promotes high-level discussion among Canada’s government, academic, corporate, and community leaders through conferences and roundtables; and supports graduate and post-graduate students to build Canada’s cadre of municipal finance and governance experts. It is the only institute in Canada that focusses solely on municipal finance issues in large cities and city-regions.

IMFG is funded by the City of Toronto, the Regional Municipality of York, the Regional Municipality of Halton, Avana Capital Corporation, Maytree, and the Neptis Foundation.

About the Urban Policy Lab

The Urban Policy Lab is the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy’s training ground for urban policy professionals, offering students career development and experiential learning opportunities through graduate fellowships, skills workshops, networking and mentorship programs, and collaborative research and civic education projects.

Endnotes

[1] Employment and Social Development Canada, “Reports: Seniors and aging society,” webpage, last modified 2023. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/seniors-aging.html

[2] Federal, Provincial and Territorial Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors, The Future of Aging in Canada Virtual Symposium: What We Heard, June 8, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/seniors/forum/reports/future-aging-virtual-symposium.html

[3] M. Hollander, “The Continuum of Care: An integrated system of service delivery,” in M. Stephenson and E. Sawyer (eds.), Continuing the Care: The Issues and Challenges for Long-Term Care (Ottawa: CHA Press, 2020), 57–70.

[4] Statistics Canada, “Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex,” Table 17-10-0005-01, 2022. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501

[5] Statistics Canada, “Type of collective dwelling, age and gender for the population in collective dwellings: Canada, provinces and territories,” Table 98-10-0045-01, 2022. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.25318/9810004501-eng

[6] Some congregate living facilities, such as many private retirement homes, may not provide 24-hour care or receive public funding.

[7] Canadian Institute for Health Information, “How many long-term care beds are there in Canada?” June 10, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cihi.ca/en/how-many-long-term-care-beds-are-there-in-canada?

[8] Canadian Institute for Health Information, “Long-term care homes in Canada: How many and who owns them?” June 10, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cihi.ca/en/long-term-care-homes-in-canada-how-many-and-who-owns-them?

[9] Ontario Legislative Assembly, Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 39, Sched. 1, 122(1). Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/21f39#BK153

[10] Whitney Blair Berta, Condition-Dependent Adaptivity of Organizational Learning in Ontario’s Long-Term Care Industry, Ph.D. thesis (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2020). Retrieved from https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/13863/1/NQ49937.pdf

[11] For a general overview of provincial differences, see A. Banerjee, An Overview of Long-Term Care in Canada and Selected Provinces and Territories (Toronto: Women and Health Care Reform Group, Institute for Health Research, York University, 2007).

[12] See Secs. 122 and 125 of Government of Ontario, Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 39, Sched. 1. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/21f39

[13] AdvantAge Ontario, Ontario’s Municipalities: Proud Partners in Long Term Care (Woodbridge: AdvantAge Ontario, 2018). Retrieved from https://simcoe.civicweb.net/document/42676/Schedule%201%20to%20CCW%2018-069.pdf?handle=FE52E13A82A746388930C47C020BDBC3#:~:text=AdvantAge%20Ontario%20is%20the%20trusted,%2C%20and%20seniors’%20community%20services.

[14] City of Toronto, “2023 Program summary: Seniors services and long-term care,” 2023. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/8e15-2023-Public-Book-SSLTC-V1.pdf

[15] City of Ottawa, Budget 2023: Working Together for a Better Ottawa (Ottawa: City of Ottawa, 2023), 79–80. Retrieved from https://documents.ottawa.ca/sites/documents/files/2023%20Adopted%20Budget%20Book%20Part%201-AODA.pdf

[16] CBC News, “Municipality of Killarney to build, run long-term care facility,” February 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/killarney-long-term-care-1.6351518

[17] Gabriel Eidelman, Tomas Hachard, and Enid Slack, In It Together: Clarifying Provincial-Municipal Responsibilities in Ontario (Toronto: Ontario 360 and Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, University of Toronto, 2020). Retrieved from https://on360.ca/policy-papers/in-it-together-clarifying-provincial-municipal-responsibilities-in-ontario/

[18] Association of Municipalities of Ontario, Strengthening Age-Friendly Communities and Seniors’ Services for 21st Century Ontario: A New Conversation about the Municipal Role (Toronto: Association of Municipalities of Ontario, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.amo.on.ca/sites/default/files/assets/DOCUMENTS/Reports/2016/StrengtheningAgeFriendlyCommunitiesSeniorsServicesFor21stCenturyOntario20160920.pdf

[19] Government of Nova Scotia, Homes For Special Care Act, R.S., c. 203, s. 1, 2010. Retrieved from https://nslegislature.ca/sites/default/files/legc/statutes/homespec.htm

[20] See Banerjee, An Overview of Long-Term Care in Canada; Region of Queens, “Hillsview Acres,” webpage, n.d. Retrieved from https://www.regionofqueens.com/municipal-services/hillsview-acres

[21] Government of Manitoba, The Elderly and Infirm Persons’ Housing Act, CCSM c E20, 2023. Retrieved from https://canlii.ca/t/55cml

[22] Government of British Columbia, Health Authorities Act, RSBC 1996, c 180, 2016. Retrieved from https://canlii.ca/t/52tzm

[23] Jason Cabaj, Katherine Fierlbeck, Lawrence Loh, Lindsay McLaren, and Gaynor Watson-Creed, The Municipal Role in Public Health, Who Does What series, No. 4 (Toronto: Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, 2022). Retrieved from https://imfg.org/report/public-health/

[24] Government of Canada, “Working together to improve health care in Canada: Overview.” Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/shared-health-priorities.html

[25] City of Toronto, “2021 COVID-19 intergovernmental funding update,” April 7, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2021/cc/bgrd/backgroundfile-165648.pdf

[26] Government of Canada, “Development of a federal Safe Long-Term Care Act: Discussion paper,” webpage, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/programs/consultation-safe-long-term-care/document.html

[27] See Kelly G. Fitzgerald and Francis G. Caro, “An overview of age-friendly cities and communities around the world,” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 26,1–2 (2014): 1–18; Verena H. Menec, Robin Means, Norah Keating, Graham Parkhurst, and Jacquie Eales, “Conceptualizing age-friendly communities,” Canadian Journal on Aging 30,3 (2011): 479–493; City of Calgary, “About age-friendly Calgary and the seniors age-friendly strategy,” webpage, n.d. Retrieved from https://www.calgary.ca/social-services/seniors/about-age-friendly-strategy.html